Imagine a Classics department at a University where the historians never bothered to learn the Greek or Latin of the original texts and you’ll have some idea of what the study of North American antiquity has been like.

Take for example Timucua, a dead language spoken by peoples native to Florida and Georgia, unrelated to nearby native languages, but was the most widely used tongue of any in that part of the world by the time of the Spanish Colonization.

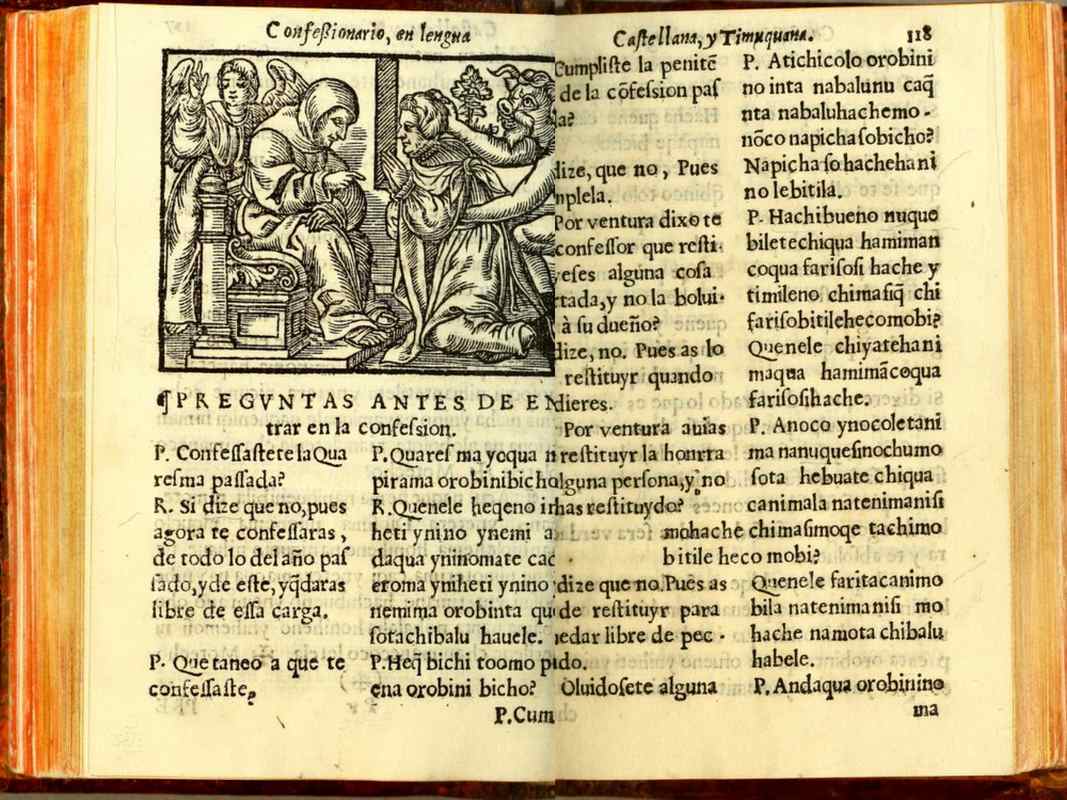

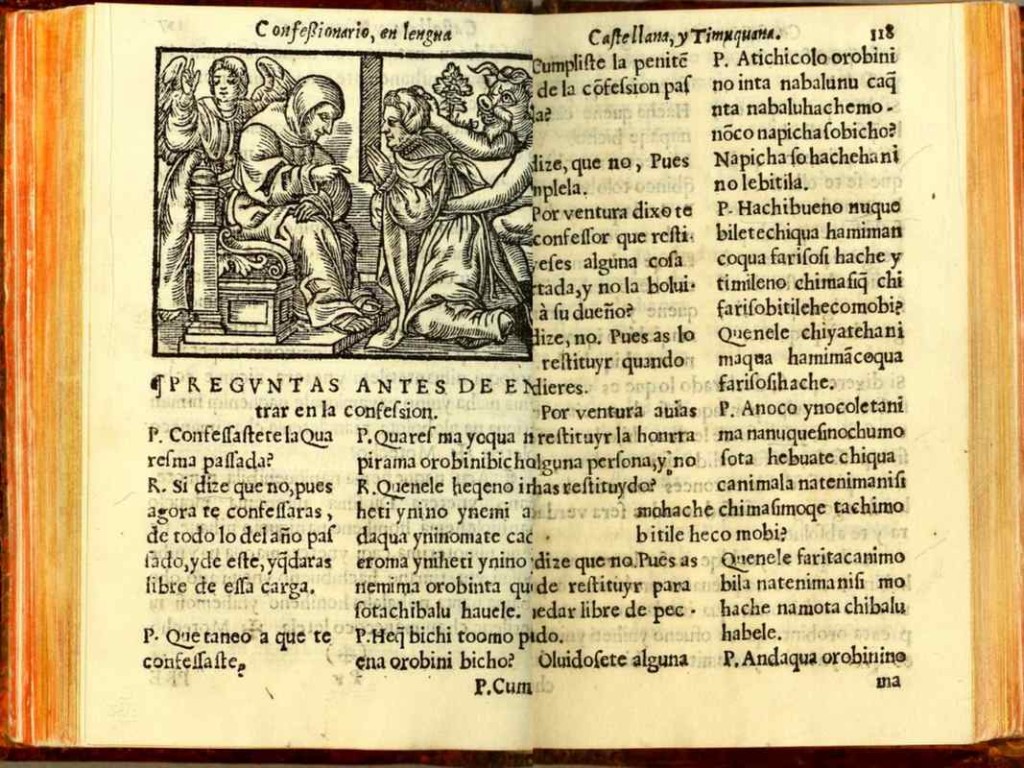

An interesting thing happened during the predictably tragic story that followed: some Franciscan priests worked to apply the Spanish-Latin alphabet to the Timucua, in order to advance education and conversion to Christianity, which gave us a written form of a Native American language from the 16th century—a rare thing.

Now, years after a pair of scholars took on the task of translating those writings, they’ve managed to create the largest database of Timucua words in history, and put the Latin and Greek back in the Classics department, to speak allegorically. They’ve also made some startling discoveries about the mental capacities of these vanished people.

Aaron Broadwell, a linguistics professor at the University of Florida, and his colleague historian Alejandra Dubcovsky, have found that the Timucua had a rather more active role in the translation of their language into Spanish than other native peoples.

“The traditional understanding of the way this works is that the missionary appears and learns the language and then translates the stuff himself,” Broadwell told the Smithsonian. “But if we look closely at the text, we can see that it didn’t happen that way.”

The Spanish texts read more like a phrasebook than a dictionary—specifically a phrasebook for priests looking to encourage the godliness of the Timucua. As a result, and much like a phrasebook written today, there are a lot of questions—however, they have more to do with implying the Timucua traditional practices are sinful than facilitating honest communication.

MORE LINGUISTIC DISCOVERIES: Ancient Grammatical Puzzle That Has Baffled Scientists for 2,500 Years Solved by Cambridge University Student

“Did you make incantations over the lake before fishing in it?” reads one.

“Do you engage in the devilish practice of whistling to the wind to make the storm stop?’” reads another.

This is where the Timucua were clearly more intelligent than the Spanish believed, because the reverse translations, as Broadwell puts it, are “considerably less judgy.”

For example, the Timucua translation to that question is “did you whistle to the wind to make it stop?” and the translation of “have the man and a woman been joined together in front of a priest?” is “did you and another person consent to be married?”

“It’s very hard to learn these languages, and Native people don’t want to share everything. And those translators aren’t given any credit,” Dubcovsky also told the Smithsonian, noting that the priests probably couldn’t understand enough of the language to double-check the translations the Timucua were making, hence why potentially ‘devilish’ practices are included in the text.

It also implies to some degree that the Timucua probably did most of the work.

MORE NATIVE AMERICAN NEWS: The ‘Sioux Chef’ Brings Indigenous Food Back to the Forefront of American Diets

Broadwell and Dubcovsky worked together on a paper examining and elaborating these findings in 2017. Broadwell also founded and curates the Timucua Dictionary, the largest and pretty much only available database on the native language.

The details that have emerged show that while unique, Timucua bears some resemblance to the Choctaw language spoken by groups nearby, and that Timucua was a complex language capable of thoroughly addressing all manner of topics.

As to the question of why Timucua didn’t have a written alphabet, Broadwell points out that for as many people as there are on the Earth, scant few have ever developed a writing system.

SHARE This Fascinating Fragment Of American History On Social Media…