The devastating tsunami that hit Indonesia so hard in December 2004 had three positive effects: it pushed the population to reflect and improve its mechanisms for managing catastrophes, it caused a new early warning detection system to be launched, and it led to the end of a conflict in the country’s Aceh province, one that had lasted 70 years.

The devastating tsunami that hit Indonesia so hard in December 2004 had three positive effects: it pushed the population to reflect and improve its mechanisms for managing catastrophes, it caused a new early warning detection system to be launched, and it led to the end of a conflict in the country’s Aceh province, one that had lasted 70 years.

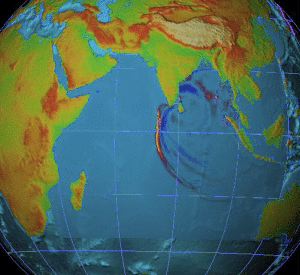

Caused by an earthquake off the coast of Aceh in western Indonesia, the tsunami sent waves reaching as high as 30 meters surging over all the lands within its reach including as far as Africa. Nearly 230,000 people in 11 countries were killed.

“After the tsunami, Indonesia’s Parliament and civil society worked together to put in place a law on the management of catastrophes, something that had never happened before,” said Titi Moektijasih, from the Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs.

As a tsunami victim herself and the sole survivor of three OCHA staff in the area, Titi, spoke today on World Humanitarian Day, explaining that even two years ago it was very difficult for her to recount her experience.

On December 26, 2004, the tsunami, already four meters high and travelling at 20 kilometers an hour, struck the centre of Banda Aceh, moving up two canals that had been dug to drain off waters from a flood in 2002.

“The tsunami made us think strategically,” she said, talking about a law created in 2007 to manage catastrophes. “The text covers a very vast field, but it is only beginning to be put into force. On the ground people have begun to rebuild and importantly a better infrastructure has been constructed.”

Titi, who visited Aceh in March 2005, September 2007, and February 2008, says she has noticed important changes in the physical aspects of the territory. She also believes that the atmosphere has changed and that people no longer live in the atmosphere of suspicion that prevailed pre-tsunami, when Government forces fought Acehnese rebels.

She also noted that resources are not lacking, either financial, or in terms of the non-governmental organizations (NGOs) involved.

A newly implemented UN-backed Tsunami Early Warning System for the Indian Ocean that went into operation in November 2008 could have saved scores of thousands of lives had it existed at the time.

“This initial system will be capable of improved and faster detection of strong, tsunamogenic earthquakes, increased precision in the location of the epi- and hypocentres of earthquakes; and confirmation of the presence of a tsunami wave in the ocean after a strong earthquake,” UN Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) Director-General Koïchiro Matsuura said.

The systems are based on quake and tidal sensors, fast communications, alarm networks ranging from radio to cell phones and text-messaging, and disaster preparedness training to ensure timely evacuation of vulnerable coastal areas.

The systems are based on quake and tidal sensors, fast communications, alarm networks ranging from radio to cell phones and text-messaging, and disaster preparedness training to ensure timely evacuation of vulnerable coastal areas.

Had one been operating in the Indian Ocean on December 26, 2004, it would have given hundreds of thousands of people several hours between the time the quake spawned the tsunami off the Indonesian island of Sumatra and its landfall in places like Sri Lanka and Thailand to flee to higher ground.

Twenty-six out of a possible 28 national tsunami information centres, capable of receiving and distributing tsunami advisories around the clock, have been set up in Indian Ocean countries. The seismographic network has been improved, with 25 new stations being deployed and linked in real-time to analysis centres.

Though greater capacity-building is needed to expand text messaging capacity and add more sirens, Mr Matsuura said, “We can be justly proud of having done all this.”

UNESCO set up the tsunami warning system in the Pacific, previously the only one fully operational in the world, in the mid 1960s.