Ripi Yanuar Fajar and his four friends say they’ll never forget the evening after Indonesia’s Independence Day celebration in 2019 when they encountered a big cat roaming a community plantation in Sukabumi, West Java province.

Immediately after the brief encounter, Ripi, who happens to be a local conservationist, reached out to Kalih Raksasewu, a researcher at the country’s National Research and Innovation Agency (BRIN), saying he and his friends had seen either a Javan leopard (Panthera pardus melas), a critically endangered animal, or a Javan tiger (Panthera tigris sondaica), a subspecies believed to have gone extinct in the 1980s but only officially declared so in 2008.

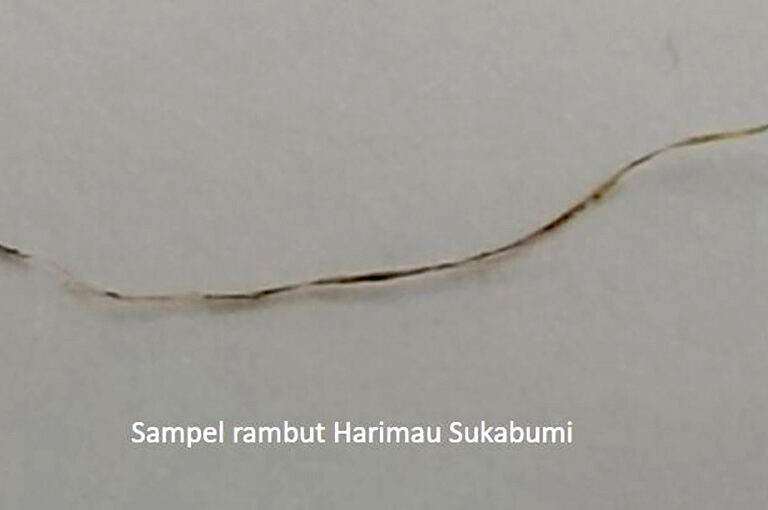

About 10 days later, Kalih visited the site of the encounter with Ripi and his friends. There, Kalih found a strand of hair snagged on a plantation fence that the unknown creature was believed to have jumped over. She also recorded footprints and claw marks that she thought resembled those of a tiger.

Kalih then sent the hair sample and other records to the West Java Provincial Conservation Agency, or BKSDA, for further investigation. She also sent a formal letter to the provincial government to follow up on the investigation request.

The matter eventually landed at BRIN, where a team of researchers ran genetic analyses to compare the single strand of hair with known samples of other tiger subspecies, such as the Sumatran tiger (Panthera tigris sumatrae) and a nearly century-old Javan tiger pelt kept at a museum in the West Java city of Bogor.

“After going through various process of laboratory tests, the results showed that the hair sample had 97.8% similarities to the Javan tiger,” Wirdateti, a researcher with BRIN’s Biosystemic and Evolutionary Research Center, said at an online discussion hosted by Mongabay Indonesia on March 28.

The discussion centered on a study published March 21 in the journal Oryx in which Wirdateti and colleagues presented their findings that suggested that the long-extinct Javan tiger may somehow—miraculously—still be prowling parts of one of the most densely populated islands on Earth.

Their testing compared the Sukabumi hair sample with hair from the museum specimen collected in 1930, as well as with other tigers, Javan leopards, and several sequences from GenBank, a publicly accessible database of genetic sequences overseen by the U.S. National Institutes of Health.

The study noted that the supposed tiger hair had a sequence similarity of 97.06% with Sumatran tigers and 96.87% with Bengal tigers. Wirdateti also conducted additional interviews with Ripi and his friends about the encounter they’d had.

“I wanted to emphasize that this wasn’t just about finding a strand of hair, but an encounter with the Javan tiger in which five people saw it,” Kalih said.

“There’s still a possibility that the Javan tiger is in the Sukabumi forest,” she added. “If it’s coming down to the village or community plantation, it could be because its habitat has been disturbed. In 2019, when the hair was found, the Sukabumi region had been affected by drought for almost a year.”

Poaching and habitat loss in Java, an island the size of Mississippi and home to more than half of Indonesia’s 270 million residents, were thought to have driven the extinction of the Javan tiger, one of three subspecies of tigers once found in Indonesia (the third is the Bali tiger, Panthera tigris balica, also officially declared extinct in 2008). The Sumatran tiger is listed as critically endangered, or one step away from vanishing in the wild, due to hunting and rapid deforestation on its native island.

MORE STORIES LIKE THIS: Farmer Saves Sickly Leopard by Carrying it to Forest Officials on His Motorbike

Rumored sightings of Javan tigers have been reported mostly by locals over the years, with the most recent one going viral in 2017, before being debunked almost immediately when the creature turned out to be a Javan leopard. Research expeditions since the 1990s have also failed to prove the continued existence of the Javan tiger.

“Through this research, we have determined that the Javan tiger still exists in the wild,” Wirdateti said. “For this reason, follow-up field studies are needed, such as observations through camera traps, looking for droppings or footprints and scratches.”

MORE BIG CAT CONSERVATION: Camera Catches Sighting of a Tiger with Cubs for First Time in 10 Years, Raising Hopes for Species in Thailand

Didik Raharyono, a Javan tiger expert who wasn’t involved in the study but has conducted voluntary expeditions with local wildlife awareness groups since 1997, said the number of previously reported sightings coupled with the new scientific findings must be taken seriously. He called on the environment ministry to draft and issue a policy on measures to find and conserve the Javan tiger.

“What’s most important is the next steps that we take in the future,” Didik said.

Republished from Mongabay on CC 4.0. License. Original authors Christopel Paino, Rahmadi Rahmad.

SHARE This Compelling Case For The Return Of A Legendary Cat…