Scientists for the first time have witnessed pieces of metal crack, then fuse back together without any human intervention, overturning fundamental scientific theories in the process.

If the newly discovered phenomenon can be harnessed, it could usher in an engineering revolution—one in which self-healing engines, bridges, and airplanes could reverse damage caused by wear and tear, making them safer and longer-lasting.

The research team from Sandia National Laboratories and Texas A&M University described their findings today in the journal Nature.

“This was absolutely stunning to watch first-hand,” said Sandia materials scientist Brad Boyce.

“What we have confirmed is that metals have their own intrinsic, natural ability to heal themselves, at least in the case of fatigue damage at the nanoscale,” he told the Laboratory’s press.

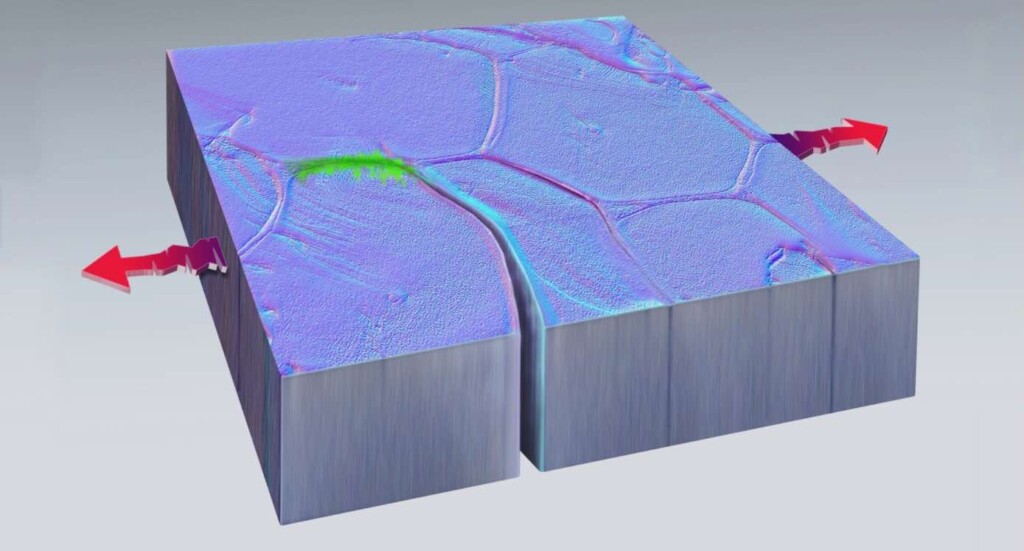

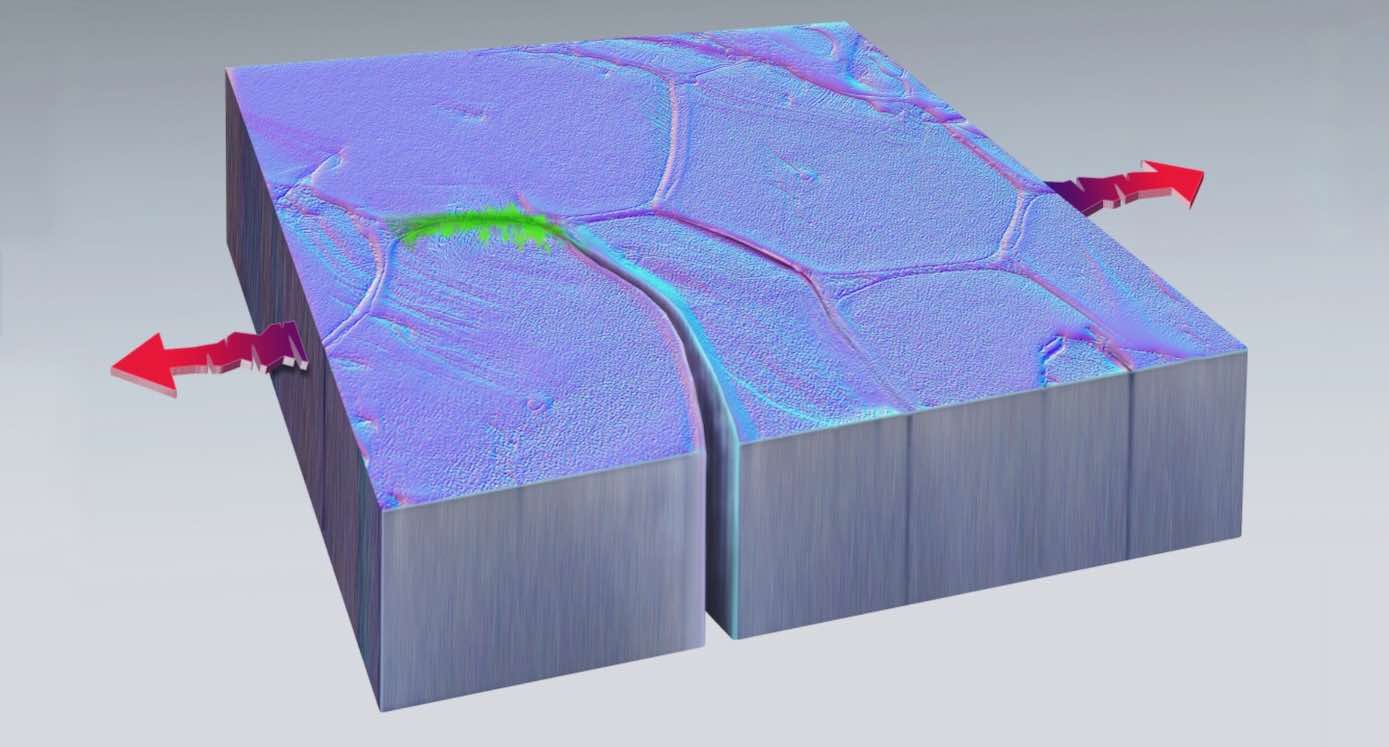

Repeated stress or motion causes microscopic cracks to form in machines’ metal components. Over time, these cracks grow and spread until the whole device breaks, or in the scientific lingo, it fails.

The fissure Boyce and his team saw disappear was one of these tiny but consequential fractures—measured in nanometers.

“From solder joints in our electronic devices to our vehicle’s engines to the bridges that we drive over, these structures often fail unpredictably due to cyclic loading that leads to crack initiation and eventual fracture,” Boyce said. “When they do fail, we have to contend with replacement costs, lost time and, in some cases, even injuries or loss of life. The economic impact of these failures is measured in hundreds of billions of dollars every year for the U.S.”

Self-healing, as much as it sounds like something from science-fiction, is actually thousands of years old. The Romans realized that making concrete with certain ingredients like lime clasts allowed it to heal itself over time.

More recently, engineers at the University of Illinois have found how to make self-healing lithium-ion batteries out of a polymer-based electrolyte that doesn’t form harmful lithium dendrites that can cause shorting and explosions.

MORE MATERIALS SCIENCE: All Kinds of Trash is Turned into Valuable Graphene That Can Cut Environmental Impact of Concrete by a Third

Khalid Hattar, now an associate professor at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, and Chris Barr, who now works for the Department of Energy’s Office of Nuclear Energy, were running the experiment at Sandia when the discovery was made. They only meant to evaluate how cracks formed and spread through a nanoscale piece of platinum using a specialized electron microscope technique they had developed to repeatedly pull on the ends of the metal 200 times per second.

Surprisingly, about 40 minutes into the experiment, the damage reversed course. One end of the crack fused back together as if it was retracing its steps, leaving no trace of the former injury. Over time, the crack regrew along a different direction.

Hattar called it an “unprecedented insight.”

MORE MATERIALS SCIENCE: Engineers Make Clear Tape 60x Stronger, Yet Still Removable, Inspired by Ancient Japanese Paper-Cutting Art

A lot remains unknown about the self-healing process, including whether it will become a practical tool in a manufacturing setting.

“The extent to which these findings are generalizable will likely become a subject of extensive research,” Boyce said. “We show this happening in nanocrystalline metals in vacuum. But we don’t know if this can also be induced in conventional metals in air.”

Yet for all the unknowns, the discovery remains a leap forward at the frontier of materials science.

SHARE This Remarkable Surprise Discovery With Your Friends…

It has been known since probably the 1500s, since the time of Durer and Rembrant, that the molecules in copper plates, used for making copper plate etchings, if left for a period (years) after they were pounded flat and made into “plates”, alighn themselves in such a way as to make the plates easier to engrave. Just because we can’t see the metal as it works its magic, doesn’t mean it doesn’t happen! Scientists should have been talking to artists, they would have possibly come across this phenomenon sooner. There is not enough of interdiscipliary research. Too many specialists with blinders on. We need broadminded scientiests to make this world right, again. Needless to say, this is, at any rate quite a discovery.