In 2006, Michelle Khine, PhD arrived at the University of California’s brand-new Merced campus eager to establish her first lab. She was experimenting with tiny liquid-filled channels in hopes of devising chip-based diagnostic tests. The trouble was, the specialized equipment she needed to make microfluidic chips cost more than $100,000 — money that wasn’t immediately available.

In 2006, Michelle Khine, PhD arrived at the University of California’s brand-new Merced campus eager to establish her first lab. She was experimenting with tiny liquid-filled channels in hopes of devising chip-based diagnostic tests. The trouble was, the specialized equipment she needed to make microfluidic chips cost more than $100,000 — money that wasn’t immediately available.

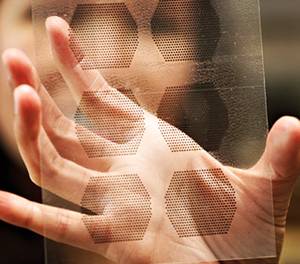

An impatient person, she began racking her brain for a quick-and-dirty way to make microfluidic devices. Khine then remembered her favorite childhood toy: Shrinky Dinks, large sheets of thin plastic that can be colored with paint or ink and then shrunk in a hot oven. “I thought if I could print out the [designs] at a certain resolution and then make them shrink, I could make channels the right size for microfluidics,” she says.

And voilà: a finished microfluidic device that cost less than a fast-food meal.

Recognizing the potential market for affordable microdevices, she helped found Shrink Nanotechnologies, which develops innovations that make micro fluidic devices more accessible to scientists without smaller budgets, speeding up important stem cell and molecular research.

(READ the story in Technology Review)