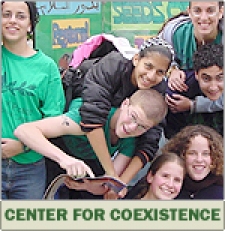

Hempstead, NY – If you were invited to sit down with your enemy for a cup of tea and discuss your conflicting views, would you do it? … More than 2,500 Israeli, Palestinian, Egyptian, Pakistani and Indian kids, among others, have done just that. In fact, they spent three weeks with their “enemies†at a summer camp in the United States arguing, understanding, and ultimately coming to respect the humanity behind every face – even the humanity of their enemies. The programme that makes this happen calls these youth, Seeds of Peace.

Hempstead, NY – If you were invited to sit down with your enemy for a cup of tea and discuss your conflicting views, would you do it? … More than 2,500 Israeli, Palestinian, Egyptian, Pakistani and Indian kids, among others, have done just that. In fact, they spent three weeks with their “enemies†at a summer camp in the United States arguing, understanding, and ultimately coming to respect the humanity behind every face – even the humanity of their enemies. The programme that makes this happen calls these youth, Seeds of Peace.

A select group of teenagers, normally forced by circumstances to take different sides in some of the world’s most intractable conflicts, have stepped away from everything they know to be true, defied the seemingly irreversible logic of ethnic and religious hatred and sat face to face with an adversary often portrayed as sub-human at home.

This quiet and unique diplomacy has been taking place at the Seeds of Peace International Camp in western Maine for over 13 years.

The programme’s strategy is simple: by forging personal bridges between adversaries, like Israelis and Palestinians, there is an immediate platform for dialogue. Taking it a step further, these parties come to know and respect each other as individuals and not just Israelis, Palestinians, Christians, Hindus, Jews or Muslims. These bonds have a tremendous ripple effect when the “seeds†return home. Their families and friends, more often than not, cannot fathom the notion of meeting the enemy to talk peace, and are eager to hear stories.

In long-standing conflicts, expired treaties, broken promises and pervasive tensions have left little room for optimism. But it’s hard to be anything but optimistic when you meet these "seeds of peace†and learn what they are doing. Armed with rare and powerful sensibility, they are embracing the fundamental values of humanity to dissipate the power of hatred and misunderstanding that lies behind their conflicts. By recognising the human face they are able to respect and talk with their enemy. These are necessary conditions for peace. Without respect there is no dialogue. And without dialogue there is no progress.

“Israel will not die and Palestine will come for sure but we need to realise our dreams without losing each other,†Yusuf Bashir, a Palestinian graduate of Seeds of Peace, said in a recent article he wrote for the organisation’s Olive Branch Magazine. A year before Bashir came to the camp he had been shot by an Israeli soldier.

A Quiet Refuge

Situated at the edge of a quiet lake surrounded by woods, the camp could be any other American summer camp, save for the international flags and the Maine State Police guarding the gate.

These “campers†often come from terrifying environments where the possibility of an explosion outside their front door is very real. Riding the bus or walking down the sidewalk entails risks unimaginable to most people.

While at the Seeds of Peace Camp these youth enjoy security, something none of them has at home. They also have the freedom to speak openly and criticise their own side’s positions without fear of reprisal from family and community. Questioning the dogmas of their society is not a luxury most of these youth enjoy. The camp is a refuge from chaos and allows for the exploration of perspectives rarely considered at home.

Campers attend “conflict resolution†sessions where they get to the heart of their differences and debate them with the opposing side. It’s not easy and nobody forgets why they are there and where they came from, but for the first time in their lives they have the chance to step outside of the environment that has so strongly shaped their views. The programme offers these kids, indeed anyone visiting the camp, a much larger perspective on their conflicts.

The Costs and Benefits When Returning Home

In 2004 I met with Zeina, a 16-year-old Palestinian, who attended the camp in Maine. She recalled the impact she felt when after returning home to Palestine she and her Israeli friend from camp met in Jerusalem along with their families. Her uncle no longer speaks to her immediate family. “He couldn’t understand,†she remarked.

As most of the Seeds of Peace staff will tell you, this is not some camp where kids hold hands, hug each other and then go home. They deal with the issues on the most basic levels. It’s humbling and profoundly educational when you listen to someone tell you why they hate you.

Seeds of Peace continues to keep in touch with participants through follow-up programmes in the home regions of the graduates.

In an interview one year after the Sept. 11, 2001 attacks in the United States, Pakistani Seeds of Peace graduate Sana Shah, then 16, was interviewed by Time Magazine. “Before going to camp, I was scared. I didn’t want to associate with Jews and Hindus,†she remarked. “But we all became good friends.†On Sept. 12, 2001 Shah wore her Seeds of Peace t-shirt to her school in Lahore, Pakistan.

Shah, like many of her fellow Seeds graduates developed a deep sense of respect for dialogue without abandoning her faith and values.

Seeds of Peace is shaping the next generation of leaders who the programme’s operators hope will be far better equipped to communicate, negotiate and resolve conflicts than their predecessors, proving that it is possible, even for those living in conflict, to overcome their circumstances and explore new paths for peace.

You may e-mail the author.