A new study has unveiled a likely future cure for HIV which uses molecular scissors to ‘cut out’ HIV DNA from infected cells.

To cut out this virus, the team used CRISPR-Cas gene editing technology—a groundbreaking method that allows for precise alterations to a patient’s genome, for which its inventors won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2020.

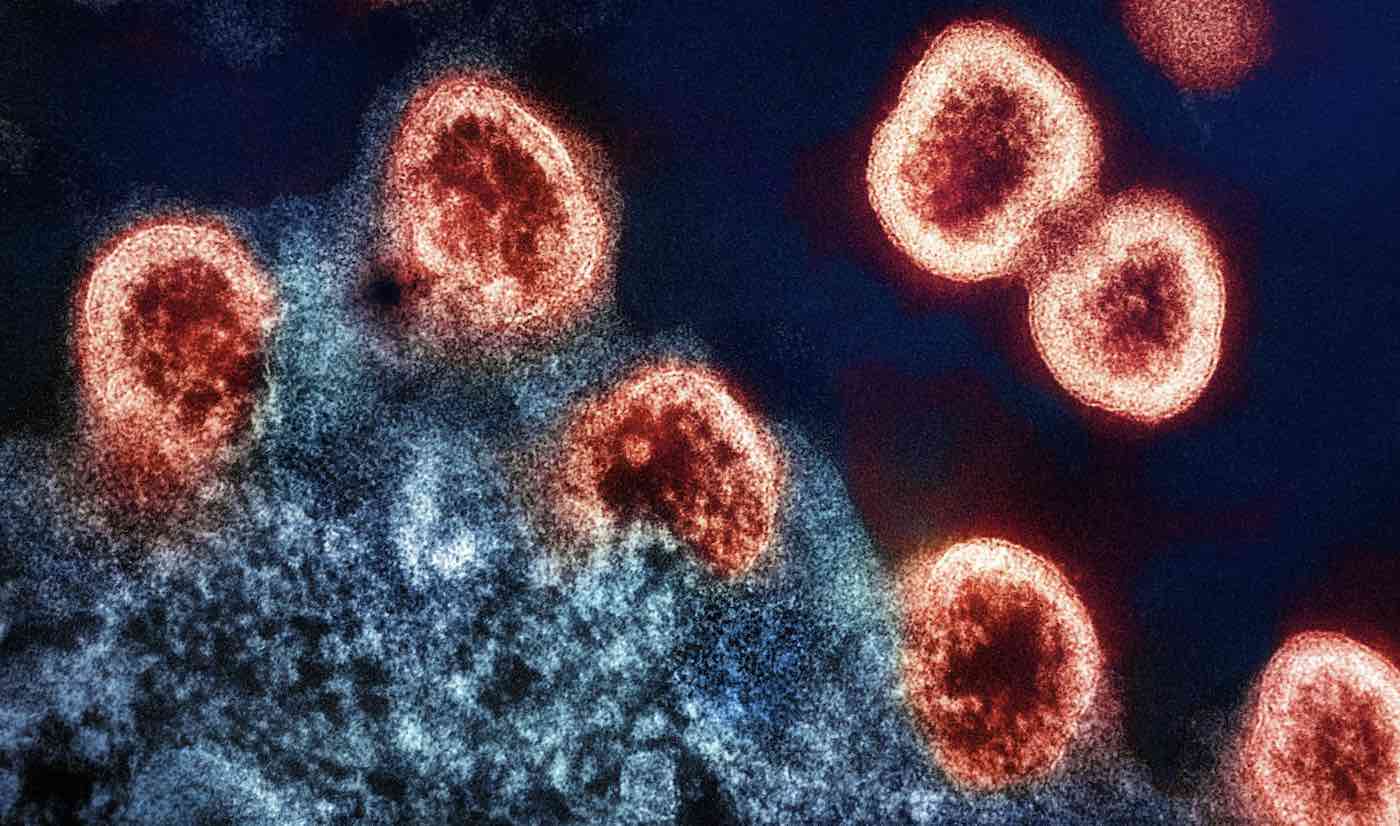

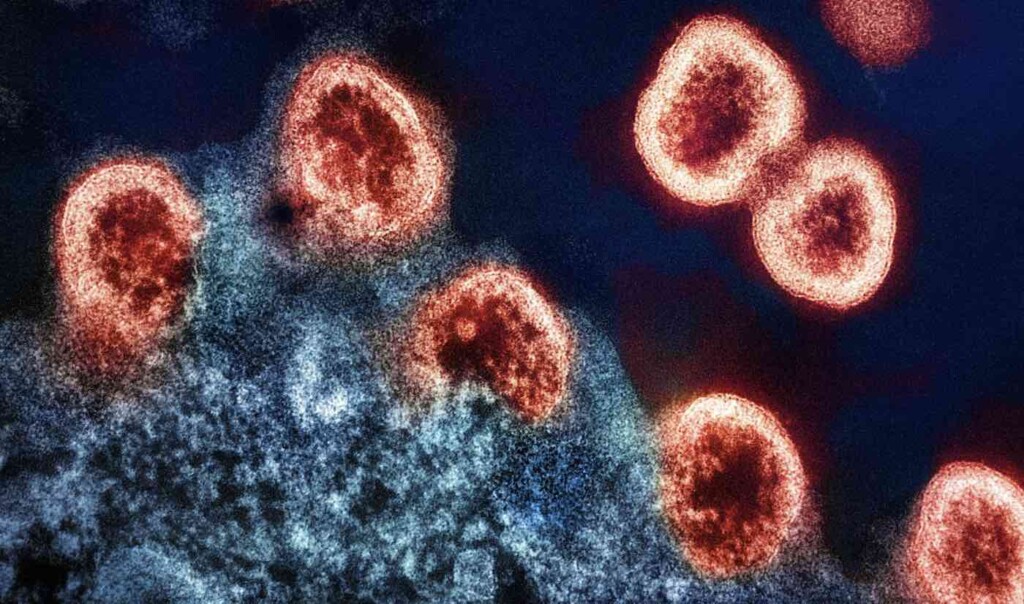

One of the significant challenges in HIV treatment is the virus’s ability to integrate its genome into the host’s DNA, making it extremely difficult to eliminate—but the CRISPR-Cas tool provides a new means to isolate and target HIV DNA.

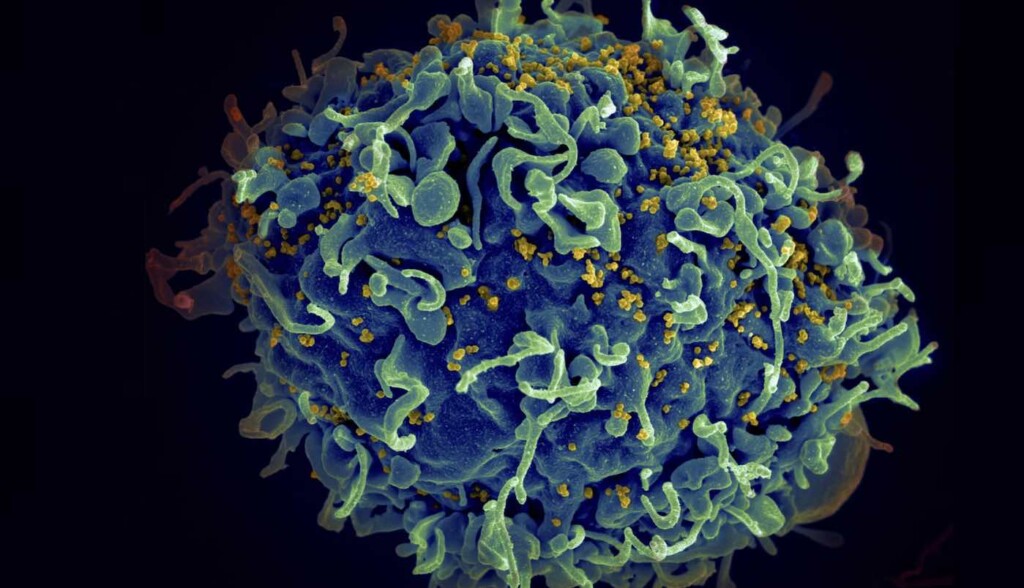

Because HIV can infect different types of cells and tissues in the body, each with its own unique environment and characteristics, the researchers are searching for a way to target HIV in all of these situations.

In this study, which is to be presented ahead of this year’s European Congress of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, the authors used CRISPR-Cas and two guide RNAs against “conserved” HIV sequences.

They focused on parts of the virus genome that stay the same across all known HIV strains and infected T cells. Their experiments showed outstanding antiviral performance, managing to completely inactivate HIV with a single guide RNA and cut out the viral DNA with two guide RNAs.

CRISPR HOPE FOR CANCER: Aggressive Leukemia Disappears in 13-Year-old Girl Who was First to Receive New CRISPR Treatment

“We have developed an efficient combinatorial CRISPR-attack on the HIV virus in various cells and the locations where it can be hidden in reservoirs, and demonstrated that therapeutics can be specifically delivered to the cells of interest,” said Associate professor Elena Herrera Carrillo from the University of Amsterdam AMC.

“These findings represent a pivotal advancement towards designing a cure strategy.”

The team has a long way to go before their cure will be available to patients, but said, “These preliminary findings are very encouraging’.

Currently, HIV can be kept in check with anti-retroviral medication, but no one has actually been cured—although three patients receiving stem cell transplants for blood cancer were subsequently declared free of the disease when their HIV became undetectable.

“We hope to achieve the right balance between efficacy and safety of this CURE strategy,” said Dr. Carrillo. “Only then can we consider clinical trials of ‘cure’ in humans to disable the HIV reservoir.

“Our aim is to develop a robust and safe combinatorial CRISPR-Cas regimen, striving for an inclusive ‘HIV cure for all’ that can inactivate diverse HIV strains across various cellular contexts.

SPREAD THE GOOD NEWS by Sharing on Social Media…