In the fantasy genre, it’s popular for writers to invent some kind of special, magical material, such as “Valerian steel” from the Game of Thrones series, or Frodo Baggins’ mithril chainmail in J. R. R. Tolkien’s writings.

Now in Bangladesh, a lost art of weaving that once created the most spectacular fabric the world had ever known is being revived, bit by bit and full of improvisations, to restore a piece of intangible cultural heritage and the national pride of a nation.

The material in question is called Dhaka muslin, and a feature piece by the BBC explains why one would be excused for thinking its story was pulled from The Lord of the Rings.

Described in texts thousands of years old, Dhaka muslin is an ultra fine, ultra soft fabric made from a potentially extinct species of sorry-looking cotton that grows along the banks of the holy Meghna River. The cotton, known locally as phuti karpas, was very delicate, snapped and frayed easily, and could only be finagled under conditions of extreme—sometimes artificially enhanced—humidity.

Eventually though, somewhere in the mists of time, ancient Bangladeshi weavers managed to convert this unseemly plant into the height of luxury fabrics, one which adorned Greek statues, Mughal emperors, the aristocracy of Europe, and even the empress of France, Josephine Bonaparte.

Its principal properties were its lightness and transparency. It was termed “woven air” by the Mughal, and described by one Dutch traveler in the 1700s as being “made so fine that a piece of twenty yards in length or even longer could be put into a common pocket snuff box.”

MORE: Garment Workers Are Now Being Educated in Bangladesh So They Can Go to College

However the subjugation of local master weavers who passed the secret of creating this fabric through the generations by the British East India Company resulted in many of the techniques being lost—even to this day, and the scraggly cotton, no longer needed, receded into the wilds.

The muslin revival

It’s not uncommon that history and progress don’t always march arm and arm, and despite our technological brilliance today, the secrets of those weaver families in ancient Dhaka have not been restored.

One man, however, is on the path of reestablishing the Dhaka muslin trade as the world’s top textile.

RELATED: Mountains of Garbage in Russia are Being Turned into Fashion

Saiful Islam runs Bengal Muslin, a heritage crafting enterprise seeking to adapt the ancient techniques and restore the phuki karpas cotton plant. He got started down this path in 2013 when the company he was working for asked him to adapt an English exhibition on the material for Bangladeshi viewers.

Born in Bangladesh, Islam felt he needed to do his own research, which resulted in several cultural exhibitions, a book, and a film commission, all of which led him and his colleagues to feel that it was perhaps possible—if only they could find the unique cotton—to restart the craft industry around the legendary fabric.

Indeed he did, and Bengal Muslin, his project dedicated to the fabric’s revival, now sells the real deal to buyers around the world, while also attending and hosting numerous events celebrating the craft.

However none of this would be possible if phuki karpas was unlocatable, and Islam had to sequence its DNA from a single pressed specimen from the 19th century kept at the Royal Botanic Gardens.

CHECK OUT: Mountains of Garbage in Russia are Being Turned into Fashionable Accessories

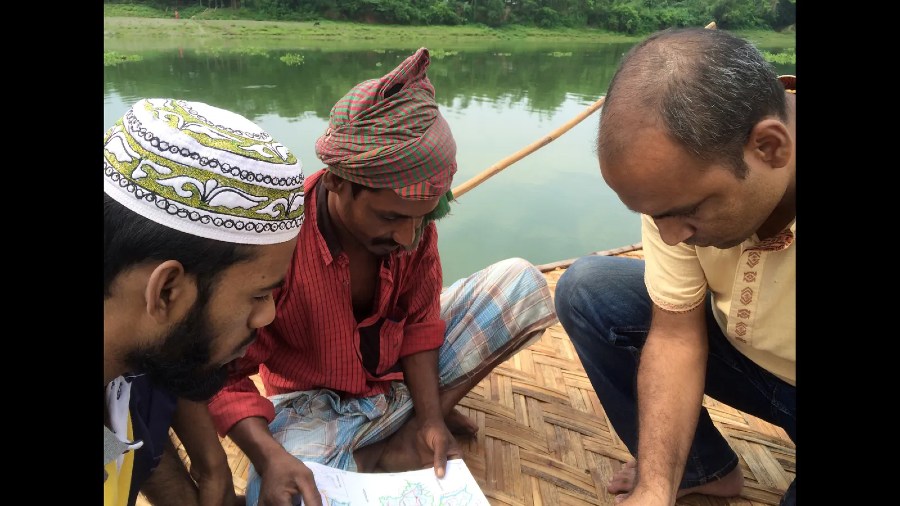

Then sailing up and down the Meghna River, a major feeder for the Ganges, he snapped up anything that looking like the pressed picture, and eventually managed to find a plant that had about three-quarters of the same genetic code—an ancestor, perhaps.

Cultivating it on an island in the middle of the river, Islam managed to produce enough to spin a thread using many improvisations to make up for the lack of ancestral knowledge. The next part was finding someone to weave the thread into a fabric.

National prestige

However Dhaka muslin’s historical value didn’t translate to willing employees, strangely enough, particularly due to the demand for high thread count. Gowns and dresses preserved in British and French museums and private collections have thread counts of 800-1,200, compared to modern cotton muslin of between 40 and 80 threads.

MORE: H&M In-Store Recycling Machine Turns Old Clothes into New Threads—A World First

“None of them [the weavers] wanted to work on this, as a matter of fact,” Islam tells Zaria Gorvett of the BBC. “They all said that this is crazy. They said: ‘Thank you very much for telling us that story and heritage, but no thanks’.”

They did eventually find a weaver of traditional Jamdani muslin, and together they were able to create a Dhaka muslin cloth with a thread count of about 300 fibers per square inch. Their first few traditional shirts, called saris, were sold for thousands of dollars, and Islam is inspired that the legend of the fabric’s quality is alive and well.

“In this day and age of mass production, it’s always interesting to have something special. And the brand is still powerful,” he says. “It’s a matter of national prestige. It’s important that our identity is not poor, with a lot of garment industries, but also the source of the finest textile that ever existed.

Featured image: Bengal Muslin

WEAVE a Little Good News For Your Friends—Share This Story…