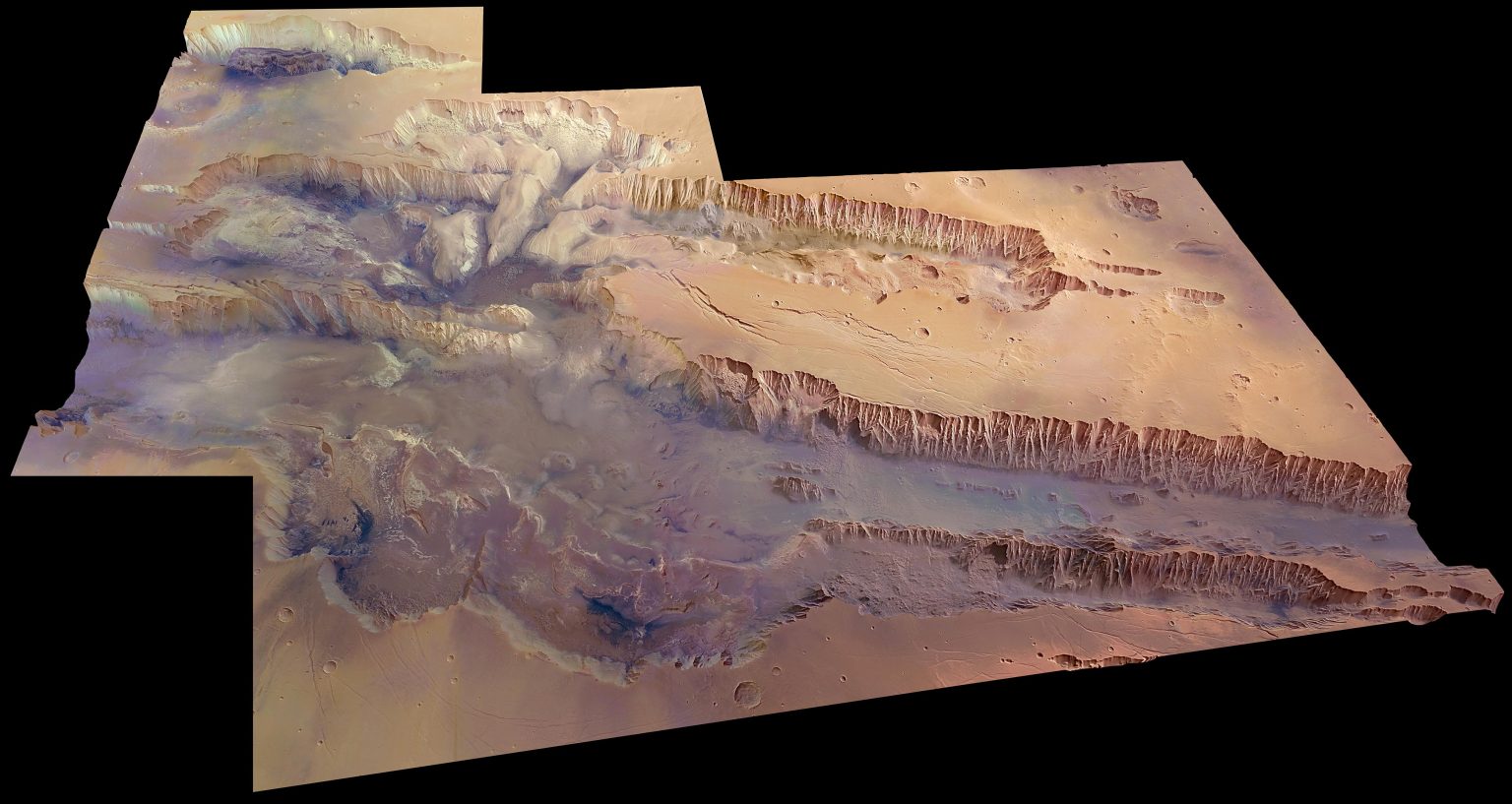

Scientists peering into the depths of Mars’ own grand canyon have found that water makes up as much as 40% of the ground there, an enormous amount considering its near to the hot dry equator of the Red Planet.

Covering 15,800 square miles (41,000 square kilometers), the area of water is larger than the Netherlands.

While Mars once had huge oceans, the particles of ice or hydrated minerals found in the top soil outside the polar reaches are all the traces that remain. 40% shatters any previous estimations of the potential for water to be found outside of the icy poles.

“We found a central part of Valles Marineris to be packed full of water—far more water than we expected,” said Alexey Malakhov, a scientist at the Space Research Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences in Moscow. “This is very much like Earth’s permafrost regions, where water ice permanently persists under dry soil because of the constant low temperatures.”

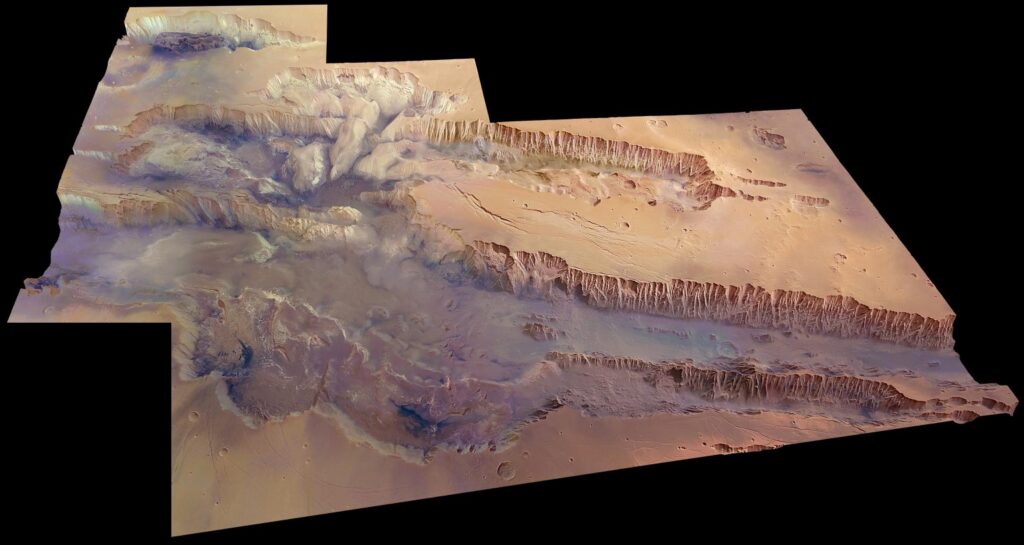

However, peering into the depths of the Valles Marineris, the solar system’s largest canyon, which is 10 times longer and five times deeper than the Grand Canyon of the Colorado River, can’t be done with just any instrument.

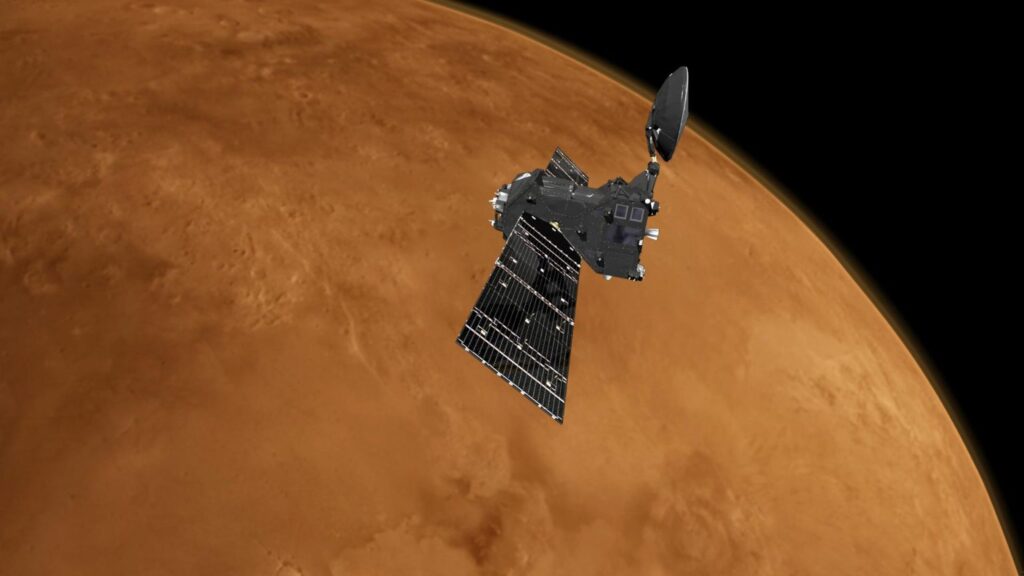

The researchers used the Trace Gas Orbiter, a joint research project by the European Space Agency and Roscosmos, its Russian counterpart. Onboard, a device for recording neutrons exiting the soil of a planet needed about three years of recordings before producing the discovery.

Neutrons are deposited in the soil of the Valles Marineris, says Malakhov, through galactic cosmic rays, and more of them make their way out again through drier soil than through moist soil. And so a lack of neutrons can be a sign that water is present.

RELATED: Spectacular Time Lapse Shows the Hypnotic Flames on the Surface of the Sun (WATCH)

The discovery is exciting for several reasons. One, unmanned missions to Mars tend to focus on the equatorial region, where the canyon and its water are located.

Secondly the water, which the researchers presume exists as ice, can be found at one meter below the surface, compared to water at the polar regions which cannot be reached unless one brings equipment to drill or blast their way down around a kilometer.

“Such ice not only is an intriguing material for searching frozen proto-life fragments or complex organic molecules from the early epoch of Mars, but also is an indispensable natural resource for future Mars exploration that is easy to exploit,” Malakhov and his co-authors wrote in their corresponding paper, published in Icarus.

SHARE This Far-Our Red Planet News Far and Wide…