Polyethylene, one of the most common plastics used today, is actually very similar in chemical structure to the chief fatty acid in soap, and a scientist at Virginia Tech has discovered a long sought-after way to convert one into the other.

The compound, called a surfactant, is now being seen as an effective way to upcycle polyethylene plastics into soap, detergents, and more.

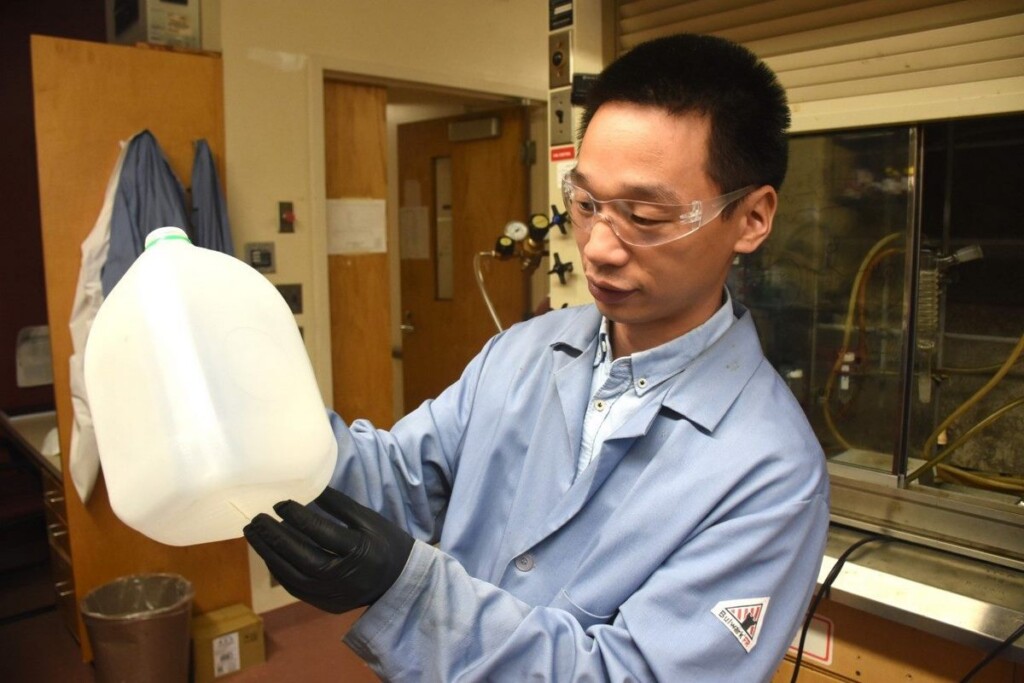

Guoliang Liu, a researcher at VA Tech, felt that there must be some way to divide the long polyethylene chains into shorter, but not too short, fatty acid chains that could be used to make soap.

Liu believed there was the potential for a new upcycling method that could take low-value plastic waste and turn it into a high-value, useful commodity.

Having considered the question for some time, Liu was struck by inspiration while enjoying a winter evening by a fireplace. He watched the smoke rise from the fire and thought about how the smoke was made up of tiny particles produced during the wood’s combustion.

Although plastics should never be burned in a fireplace for safety and environmental reasons, Liu began to wonder what would happen if polyethylene could be burned in a safe laboratory setting. Would the incomplete combustion of polyethylene produce “smoke” just like burning wood does? If someone were to capture that smoke, what would it be made of?

“Firewood is mostly made of polymers such as cellulose. The combustion of firewood breaks these polymers into short chains, and then into small gaseous molecules before full oxidation to carbon dioxide,” said Liu.

MORE CHEMICAL UPCYCLING: Breakthrough: Polyethylene Bags and Jugs Can Finally be Upcycled to Solve Several Problems at Once

“If we similarly break down the synthetic polyethylene molecules but stop the process before they break all the way down to small gaseous molecules, then we should obtain short-chain, polyethylene-like molecules.”

Two Ph.D. chemistry students in Liu’s lab aided the curious researcher in building a laboratory oven for the experiement, where they could heat polyethylene in a process called temperature-gradient thermolysis. At the bottom, the oven is at a high enough temperature to break the polymer chains, and at the top, the oven is cooled to a low enough temperature to stop any further breakdown.

After the thermolysis, they gathered the residue—similar to cleaning soot from a chimney—and found that Liu’s hunch had been right: It was composed of “short-chain polyethylene,” or more precisely, waxes.

MORE CHEMISTRY BREAKTHROUGHS: Life-Saving Breakthrough for Antibiotics Uses Shapeshifting Chemistry that Won 2022 Nobel Prize

This was the first step in developing a method for upcycling plastics into soap, Liu said. Upon adding a few more steps, including saponification, the team made the world’s first soap out of plastics. To continue the process, the team enlisted the help of experts in computational modeling, economic analysis, and more.

“Our research demonstrates a new route for plastic upcycling without using novel catalysts or complex procedures. In this work, we have shown the potential of a tandem strategy for plastic recycling,” said Zhen Xu, lead author on the paper published in Science, and one of the Ph.D. students. “This will enlighten people to develop more creative designs of upcycling procedures in the future.”

SHARE This Awesome Bit Of Chemistry With Your Friends…