A passionate expert on fungi has spent a decade trying to discover the identity behind a preserved and mislabeled specimen in an Australian collection—all for the sake of science.

Despite being one of the 5 kingdoms of life—alongside animals, plants, and two kinds of microorganisms—mycology, or the study of fungi, is not only a niche field, but a shrinking one.

At the National Herbarium in Melbourne, Australia works Tom May, the institution’s principal research scientist in mycology.

He’s a man for his place and time, to quote The Big Lebowski, and has worked for decades studying and identifying various fungi—and none presented a greater challenge than a small sample of wood and fungus contained within a handmade blue envelope dating back over a century.

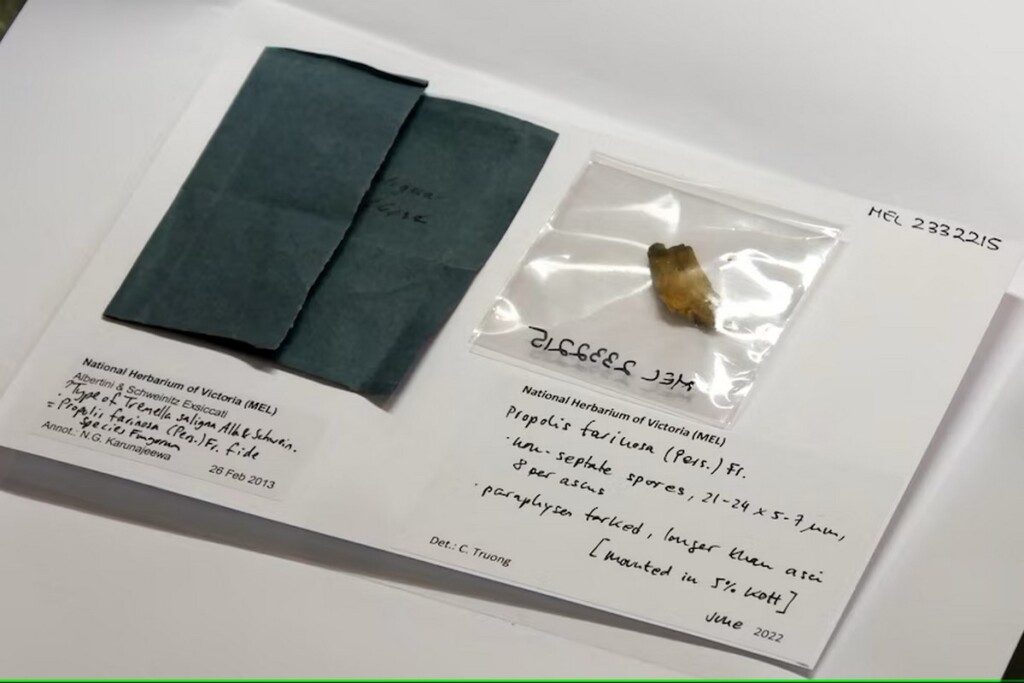

It was donated to the Herbarium by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Victoria, and inside Dr. May found some small shriveled mushroom samples bearing only an untraceable name.

Dr. May opened that blue packet a decade ago, and unraveling the mystery of the sample therein required a masterclass in scientific sleuthing that took him all over Europe.

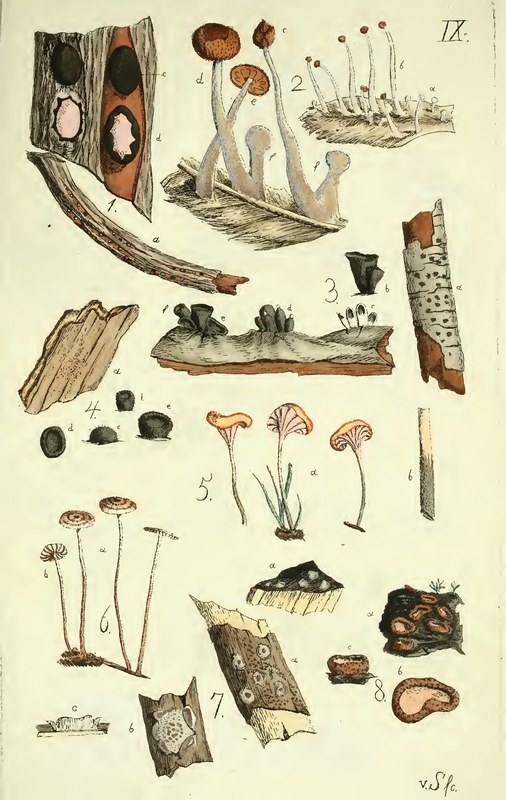

For all the time spent sifting through what were probably inventory records, May’s closest encounter while trying to identify the mysterious old sample was a book by a German researcher published in Latin back in 1805.

A team of German scientists wrote the Conspectus fungorum in Lusatiae superioris, in which they documented 1,000 samples of mushrooms and molds found near the border between Germany and Poland. The blue packet contained the name Tremella saligna, and Dr. May believed it was one of around 300,000 specimens obtained by the then-Government Botanist of Victoria in 1883.

Finding out more was “sort of like putting bits together of a jigsaw”, May told ABC News Down Under.

Why it’s important

Today, searching for species by taxonomy is an invaluable resource for scientists studying life on Earth. Regardless of the scientist’s spoken language, they can communicate with each other, read inventories and papers, and conduct research, all in Latin—as taxonomy uses Latin exclusively.

Plants, birds, and especially fungi, often take on numerous colloquial names by local cultures, causing confusion as groups of people in the same country—even using the same language—will give different nicknames to the same species.

Even though it bore a Latin name, it was no straightforward thing for scientists so long ago to alert all of Europe that, for example, they had found a small tree-growing mushroom in Germany and officially named it.

MIND-BLOWING MUSHROOM DISCOVERIES:

- Stanford Designer is Making Bricks Out of Fast-Growing Mushrooms That Are Stronger than Concrete

- The Myriad of Massive Health Benefits in 6 Different Kinds of Mushrooms

- Scientists Have Used Mushrooms to Make Biodegradable Computer Chip Parts

- Porcini Mushrooms Rank Among Highest in the World for Rare ‘Essential Vitamin’

- Mushrooms Help Turn Toxic Brownfields into Blooming Meadows

For that reason, May had to travel to the USA and Germany to confer with scientists about whether the specimen held in the Herbarium was the same as in the book. In Germany however, he found a handwritten list created by one of the book’s authors: Johannes Baptista von Albertini.

“We were thrilled to see that the handwritten names in Albertini’s list and on the specimens exactly matched,” Dr. May said.

Sure enough, the species had been catalogued even before Albertini’s 1805 publication as Propolis farinosa. ABC News described it as being like a phone book with the same person listed at two different addresses and numbers. Whoever logged it in the National Herbarium back in 1883 had taken the name from Albertini’s publication, one which mycology more broadly, had left behind.

The species has now been described, genetically mapped, and unified internationally as P. farinosa. Dr. May has also been recognized internationally, and inducted as a Fellow into the International Mycological Association for his outstanding contributions to mycology.

There are 150,000 species of described fungi, but there may be as many as 3.5 million out there yet to be discovered. Fungi—which contain both the lifeforms that produce mushrooms and molds—are thought to represent a pharmacological gold mine. Having already provided a little something called “penicillin” to medical science, fungi show strong natural anticancer effects—and mycologists like Dr. May say it is a key area to search for new medicines.

SHARE This Wonderful Story Of A Passionate Man’s Work For The Benefit Of Humanity…