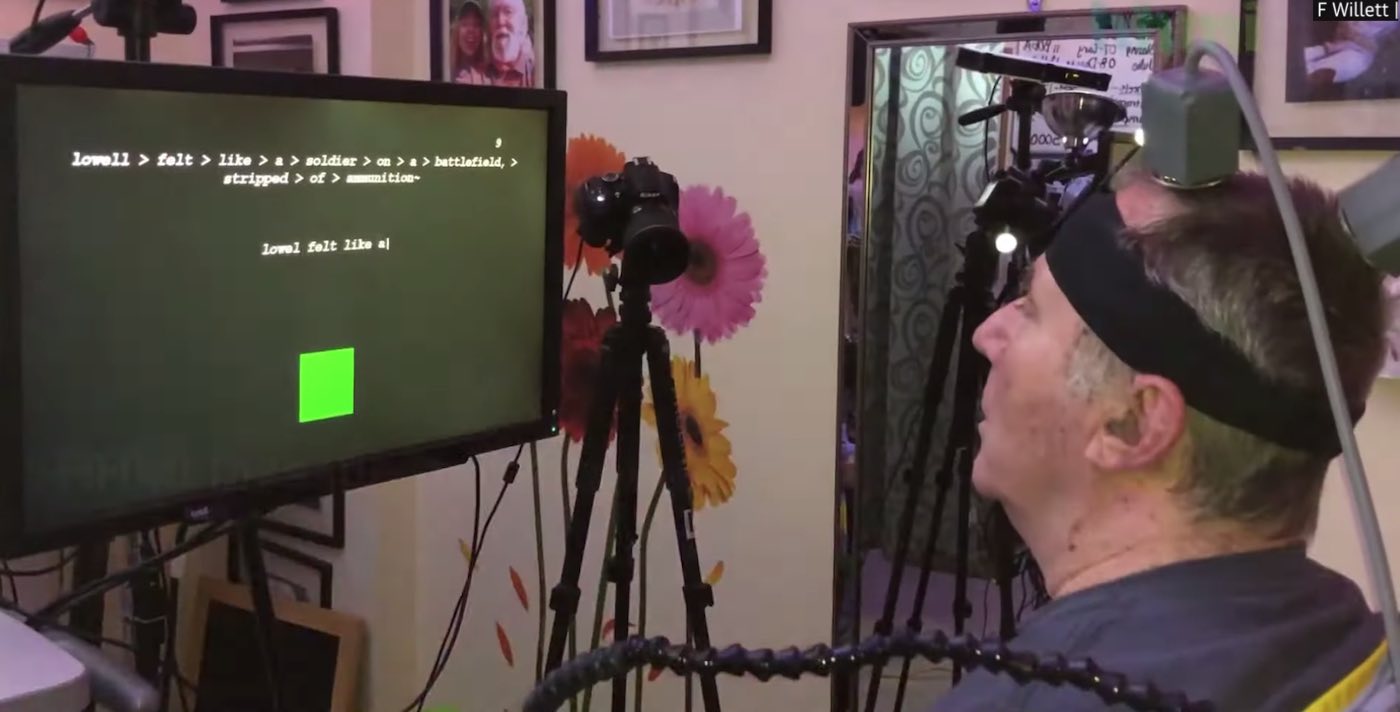

A man paralyzed from the neck down has gained the ability to type words with his brain about as fast as the average smartphone user, a new study says.

This “mindwriting” was done through a science-fiction sounding brain-computer interface (BCI) that picked up neural signals and fed them into an algorithm which translated them into letters.

The secret to the success, and why this particular BCI was able to produce words at such a faster rate than other BCI’s in the past, was that it tracked the brain signals of the patient, known as T5, as he imagined writing them down with a pen—a skill which imprints so thoroughly on our motor skill system that it remains for years after paralysis evidently.

The man was 65 at the time of the study, but it was 2007 when he suffered his spinal cord injury.

“With this BCI, our study participant achieved typing speeds of 90 characters per minute with 94.1% raw accuracy online, and greater than 99% accuracy offline with a general-purpose autocorrect,” wrote the authors, whose paper can be read in Nature. “To our knowledge, these typing speeds exceed those reported for any other BCI, and are comparable to typical smartphone typing speeds of individuals in the age group of our participant”

MORE: He Designed a Mountain Bike to Bring Adventure Back to People With Disabilities – Like Himself

Conducted by Stanford University and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, the most common error the machine made was with lowercase letters of similar shapes, such as ‘r’, ‘h’, and ‘n’.

At first they allowed the patient to write each letter as he would with his hand, and eventually moved to asking him questions, allowing him to write out his responses—which pleased him no end, they told NPR.

Some BCIs and other machines that are designed to allow paralyzed people to write typically track eye movement, which is often retained even in the most extreme cases of paralysis, such as with the famous locked-in syndrome patient Jean-Dominique Bauby. Bauby is known for writing The Diving Bell and the Butterfly, published in 1997, which he composed entirely through the painstaking process of blinking upon an aid’s selection of the correct letter.

Stanford had conducted other trials with different BCIs before, in which they used eye-monitoring equipment, but found it required tremendous attention and focus from the user.

RELATED: Scientists Demonstrate Success of a Possible ‘EpiPen’ to Prevent Paralysis From Spinal Cord Injuries

The new BCI isn’t yet developed enough to be called a prototype, meaning it will likely be years before more paralysis victims can regain their ability to communicate. However, this also means the room for refinement is much higher, explained one scientist, speaking with CNN.

SHARE This Breakthrough Research With Pals on Social Media…