While the summers may be getting hotter, there have always been people living in the deserts and the tropics, and some of their architectural designs from eras past could hold the key to keeping cool in today’s changing climate.

Emissions from buildings are the largest sources of anthropogenic CO2 in society, and a large chunk of that comes from air conditioning. Prior to electricity however, India under the Mughal Empire, or the Ancient Persians had ways of keeping cool that combined simple physics with beautiful architectural design.

Today, these cultures are providing inspirations to building managers and architects who want to design buildings that stay cool without as much reliance on air conditioning.

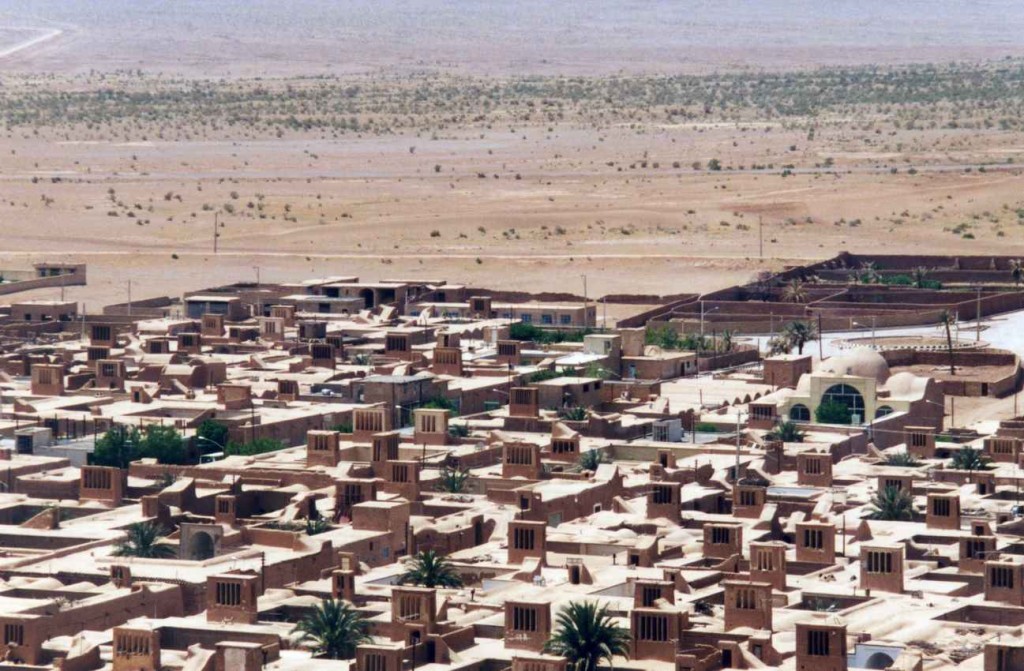

One such method is the wind catcher, which if you fancy a drive through Andalusia’s new housing units, or the ancient Persian city of Yazd, or even past the Royal Chelsea Hospital in London, may appear like chimneys.

In reality, they are ingenious structure that make use of the desert winds, and the basic differences between the properties of hot and cold air, to cool building interiors. Stretching up from the roof, the openings in the towers catch the breeze which is channeled via a series of curved walls down into a chamber below.

Dust or debris is traditionally left by the breeze at the bottom of the tower, which would simply be a room inside the house. Then the density of the cold air, which naturally means it will sit lower than hot air which rises, disperses throughout the interior while using that density to push the hot air out through another tower.

The ancient Persians perfected this art, and the grandiose result of this is found in the ancient city of Yazd on the hot, dry, Iranian plateau, recognized by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site for its wind catchers.

SIMILAR: Eco-friendly Chinese ‘Amateur’ Wins Most Prestigious Architecture Prize

In some of the larger structures, they would pair their wind catchers with sophisticated aqueducts. The towers once deposited the captured breeze in subterranean chambers of water, cooling it yet further.

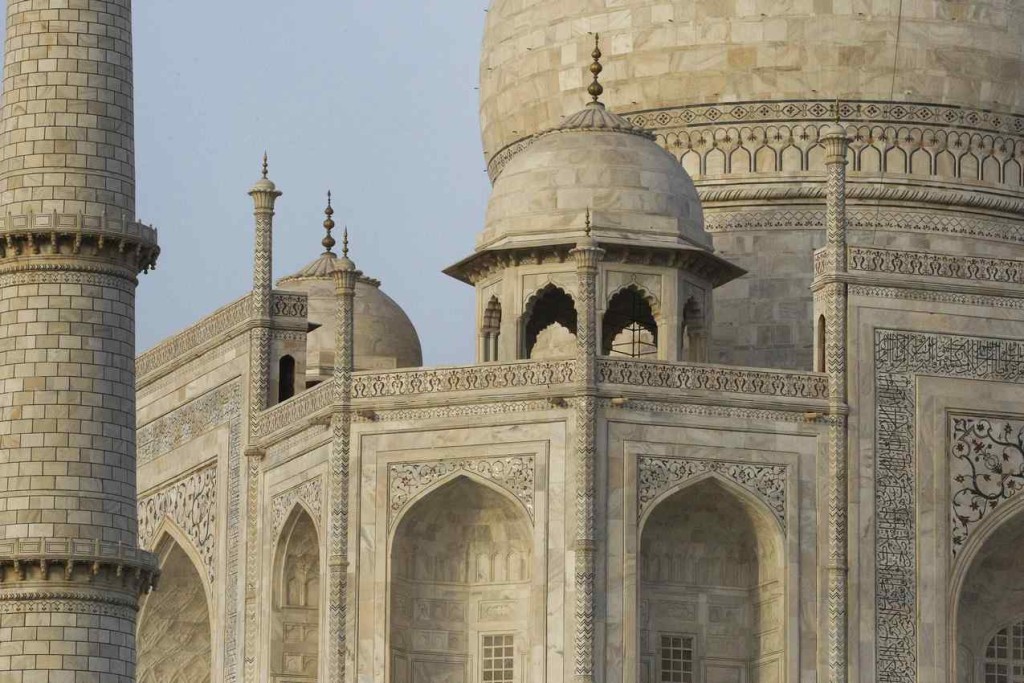

These wind catchers can be found all over the Islamic world, but they are believed to have reached their creative, decorative, and functional pinnacle in Iran. But other cultures have contributed non-mechanical cooling methods as well, and to see them one needs look no further than the Taj Mahal.

Simple physics

The traditional lattice-work marble screens, or jaali, on the windows of the Taj Mahal and other ornate Indian buildings are gorgeous to behold, and cool to stand behind. The intricately-carved lattice actually prevents around 70% of thermal energy of the sun from entering the palace rooms.

Normally carved from red sandstone or marble, it defuses lighting, provides necessary privacy, lets in breeze, but keeps out direct heat, making them ideal for façade that face the sun’s path.

Relying on simple physics, the jaali of the Mughal period are now being widely adopted today to reduce the cooling burden on air conditioning.

The Venturi effect shows that as air moves from a large space into and through a narrow space, it must not only cool, but also speed up. The holes in the jaali not only let in air, but actively cool and push it into the interior. Wooden jaali can be used in dryer climate to improve humidity in buildings. At night, air passing through the cooled holes deposits small amounts of moisture that is later expressed into the interior during the following day.

READ ALSO: Architecture Built 1,000 Years Ago to Catch Rain is Being Revived to Save India’s Parched Villages

Like the wind catchers, many architects today are using these jaali as a method of adapting modern buildings to climate change. Often called a building’s “envelope” meaning a super-structure that separates the interior façade from direct sunlight, many of the design principles replicate the Indian jaali. These can be found at the Nakâra Residential Hotel on Agde, Greece, the Cordoba Hospital in Cordoba, Spain, and the Al Bahr towers in Abu Dhabi.

Jaali have been found to reduce the reliance on air conditioning by 35% in some cases, and like the wind catchers of Ancient Persia, show us that not all problems need modern solutions. Sometimes the accomplishments of the past are enough for the challenges of the future.

SHARE These Innovative Cultures’ Solutions With Your Friends…