Nothing in Oprah Winfrey’s life has made her prouder than creating her school for girls in Henley-on-Klip, South Africa. And nothing, she says, has given her more headaches.

Nothing in Oprah Winfrey’s life has made her prouder than creating her school for girls in Henley-on-Klip, South Africa. And nothing, she says, has given her more headaches.

The scope of her vision is immense: to help students who grew up amid poverty, abuse and trauma not only to graduate from high school, but to go on to college and become South Africa’s leaders. Her donation was just as spectacular: $40 million went into building the 52-acre (21-hectare) campus of the Oprah Winfrey Leadership Academy for Girls.

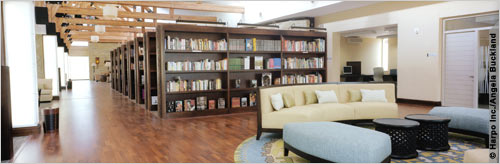

But since the project was announced, critics have questioned the lavishness of the school’s yoga studio, original art works and dorm rooms with expensive sheets. Less than a year after the school opened in 2007, a dormitory matron was charged with abusing students. Then there have been the day-to-day struggles of staffing the school and taking care of the girls, who still have real problems.

“It’s very easy to get caught up in the spirit of the emotionalism of philanthropy — ‘I want to help, I want to save, I want to change’ — and not be grounded in the structure and infrastructure that is required for the execution of your dream,” Winfrey said in an interview with America.gov. “I was starting with, ‘Ah, I want to build the school — I love the children!’”

Winfrey said she has learned from the experience of the academy. She has not downgraded her ambition; she has just realized the practical difficulties that dog even the best of intentions. “My goal,” she said, “is to get this right.”

Winfrey’s difficulties are not unusual, given the magnitude of her undertaking, said Brad Smith of the Foundation Center in New York, which collects research on organized philanthropy. He said nearly all aid projects undergo a “mid-course correction,” and donors have to be self-critical about the work and open to change. “Philanthropy is something you learn by doing,” he said.

For Winfrey, the easiest part of the endeavor has been finding girls in difficult circumstances who have potential. About 3,500 girls applied for the school’s first 152 slots. Some were orphaned by AIDS, others were abandoned by parents. Two sisters had watched their father kill their mother and then commit suicide.

Many lived in homes without electricity or running water and slept on dirt floors. Yet applicants yearned for education. One girl had braved the wait at a dangerous bus stop each morning so she could get to school. Winfrey wanted to make room for all of them. “I now know you can find great girls anywhere,” she said.

Finding great teachers has been harder. Winfrey assumed that recruiting teachers like the ones who had inspired her would be easy. But in South Africa, the system of apartheid had stunted the skills of black teachers. “Everybody’s still growing in that post-apartheid era, growing into who they can be and into what is possible,” Winfrey said.

The academy’s tree-lined campus, with its state-of-the-art science labs, 600-seat theater and spacious dorms, is a world away from the girls’ old neighborhoods. In a few cases, the students have escaped negative influences at home that have not been easy to close off. Two girls had wanted to spend their holiday break at a relative’s home that school counselors consider dangerous. Winfrey personally pleaded with the girls to go to an orphanage instead. “You’ve just got to be able to hold on, hold on to yourself until I can get you in college,” she recalled telling them. “We’re just trying to keep you safe, and keep you learning and keep you growing until I can get you to college.”

The academy’s tree-lined campus, with its state-of-the-art science labs, 600-seat theater and spacious dorms, is a world away from the girls’ old neighborhoods. In a few cases, the students have escaped negative influences at home that have not been easy to close off. Two girls had wanted to spend their holiday break at a relative’s home that school counselors consider dangerous. Winfrey personally pleaded with the girls to go to an orphanage instead. “You’ve just got to be able to hold on, hold on to yourself until I can get you in college,” she recalled telling them. “We’re just trying to keep you safe, and keep you learning and keep you growing until I can get you to college.”

The school helps students navigate between their new and previous lives. Girls feel guilty that they have opportunities that their siblings and friends don’t. “We’ve worked on the guilt, we have worked a lot on the guilt,” Winfrey said. “Unless you can love and nurture and educate yourself, you won’t be able to do anything for anybody else. So it doesn’t make sense for everybody to be in the circumstance where nobody can do anything. You’re going to be the one who can do something.”

Dr. Bruce Perry of the Houston-based nonprofit ChildTrauma Academy said he never has seen a school in which the expectations of success for disadvantaged youngsters are so high.

Perhaps the biggest benefit that Winfrey brings is her life story, a story of someone who overcame the obstacles of poverty and racial prejudice. Her influence also has drawn inspiring visitors to the school, such as former South African President Nelson Mandela, Nobel Peace Prize laureate Wangari Maathai, and Gcina Mhlope, a South African freedom activist and well-known storyteller-poet.

“You can’t underestimate what it means to children when you see someone achieve excellence in an area and how they did it, how there was disappointment and how they got through it,” said Perry, who is a consultant to the school. The students see, he said, that it is not foolish to think, “‘I’m a poor little girl from South Africa, and … I can be an ambassador or anything else.’”

WINFREY STILL DREAMS BIG

Despite the challenges, Winfrey remains committed to giving an even greater number of disadvantaged girls an education. She doesn’t plan to replicate the academy exactly, but to use what she’s learned there for initiatives in other countries. While she doesn’t regret building a luxurious campus, she said she realizes now that “you don’t have to just have the bricks and mortar. There are a multitude of ways to educate girls without building.”

Her ultimate goal is to educate 100 million girls. The idea “seems like an impossible dream, but nothing’s impossible,” she said. Just look at daily life at the academy: Girls who once pumped and carried water are now playing violins. Girls who are orphans are running a community program to help other orphan children.

“The change is like the difference between living in a neighborhood where there is no hope,” Winfrey said, “to now creating a community where people feel, where all the girls feel like, ‘I’m going to college, and I will be successful for myself and my family, my community, my country.’”

Reprinted from America.gov