Nearly 60,000 books prized by historians, writers and genealogists, many too old and fragile to be safely handled, have been digitally scanned as part of the first-ever mass book-digitization project of the U.S. Library of Congress (LOC), the world’s largest library. Anyone who wants to learn about the early history of the United States, or track the history of their own families, can read and download these books for free.

Nearly 60,000 books prized by historians, writers and genealogists, many too old and fragile to be safely handled, have been digitally scanned as part of the first-ever mass book-digitization project of the U.S. Library of Congress (LOC), the world’s largest library. Anyone who wants to learn about the early history of the United States, or track the history of their own families, can read and download these books for free.

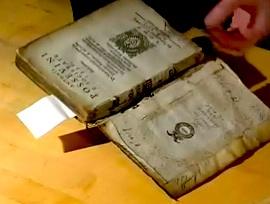

“The Library chose books that people wanted, but that were too old and fragile to serve to readers. They won’t stand up to handling,” said Michael Handy, who co-managed the project, which is called Digitizing American Imprints.

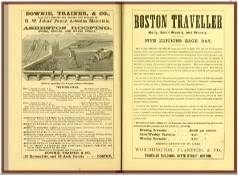

“Many of these books cover a period of Western settlement of the United States — 1865–1922 — and offer historians a trove of information that’s otherwise tough to locate,” he said. Books published before 1923 are in the public domain in the United States because their U.S. copyrights have expired.

The oldest work in the batch, dated 1707, covers the trial of two Presbyterian ministers in New York. The 25,000th book to be digitized was a 1902 children’s history book, The Heroic Life of Abraham Lincoln: The Great Emancipator, in time for Lincoln’s bicentennial on February 12, 2009.

These and the other digitized books can be accessed through the Library’s catalog Web site and the Internet Archive (IA), a nonprofit organization dedicated to building and maintaining a free online digital library.

“The Library’s collections are of unbelievable scope and depth,” said Internet Archive co-founder Brewster Kahle. “Now, with an Internet connection, you can download, print or bind copies of all these books.”

In addition to the LOC collection, IA includes content from other institutions that are part of the Open Content Alliance, a consortium of organizations around the world that seeks to build an archive of free, multilingual, digitized text and multimedia material.

HISTORY AND GENEALOGY

Many of the newly digitized LOC works contain hard-to-obtain Civil War regimental histories and county, state and regional information relating to specific people, their occupations and families, and other details that are important for historians and genealogists. Of an 1854 work by David Sutherland, titled Address delivered to the inhabitants of Bath, New Hampshire, one reader wrote, “I loved it. My two children are descendants of this gentle man. Very interesting first person accounts of early American life.”

Many of the newly digitized LOC works contain hard-to-obtain Civil War regimental histories and county, state and regional information relating to specific people, their occupations and families, and other details that are important for historians and genealogists. Of an 1854 work by David Sutherland, titled Address delivered to the inhabitants of Bath, New Hampshire, one reader wrote, “I loved it. My two children are descendants of this gentle man. Very interesting first person accounts of early American life.”

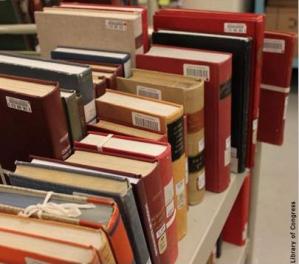

Books sit on a cart ready to be scanned for the Library of Congress mass book-digitization project. Nearly 60,000 books focusing on history and genealogy have been scanned, including many too fragile to be handled by readers. The scanned books, which are available on the Library of Congress and Internet Archive Web sites, are stored in a special facility in Maryland for safekeeping.

Another reader commented on The Causes of the American Civil War by John Lothrop Motley, published in 1861 as the war began: “This is an amazing gift for humanity! We must be thankful with the people involved in this gigantic project, which is an open door to the treasures of our history. Thank you very much for doing this.”

The Library of Congress has digitized many of its other collections — more than 7 million photographs, maps, audio and video recordings, newspapers, letters and diaries can be found at the Library’s Digital Collections site, such as the popular American Memory and the multilingual Global Gateways collections — but “this is the first sustained book-digitization project on a high-volume basis,” Handy said.

The Internet Archive is the second-largest book-scanning project after Google Books. A subset of this project is the Google Books Library Project, which has agreements to scan collections of numerous research libraries worldwide. (Google Books remains the subject of legal challenges, particularly regarding copyright issues.)

DIGITIZATION CHALLENGES

A $2 million grant from the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation inaugurated the LOC book digitization project. One of the grant’s objectives was “to address some of the issues that other book digitization projects had mainly avoided dealing with — for instance, the brittle book issue,” Handy said. “We established some procedures and preservation treatments to be able to scan books that otherwise couldn’t be scanned.” The library also worked with Internet Archive — which provided the scanning equipment — to develop a special station for scanning fold-out materials such as maps.

Before and after scanning, a librarian inspects each book for damage — what Handy calls “preservation triage.” Ten scanning specialists sit at “Scribe” scanning stations. In each Scribe, two digital cameras hover over the open book on a mechanized tabletop. The specialist positions the book for accurate scanning, snaps the digital photos with a foot pedal, then turns the page and scans the next pages. The teams can scan 1,000 volumes per week. Hours after scanning and inspection, the books are available on the Internet.

Before and after scanning, a librarian inspects each book for damage — what Handy calls “preservation triage.” Ten scanning specialists sit at “Scribe” scanning stations. In each Scribe, two digital cameras hover over the open book on a mechanized tabletop. The specialist positions the book for accurate scanning, snaps the digital photos with a foot pedal, then turns the page and scans the next pages. The teams can scan 1,000 volumes per week. Hours after scanning and inspection, the books are available on the Internet.

The Library of Congress is producing a report on best practices for dealing with brittle books and fold-out materials that it plans to post on its Web site and share with the Internet Archive and other members of the Open Content Alliance “so it’s available to anybody,” Handy added.

The scanned books are retired to an environmentally controlled storage facility at Fort Meade, Maryland, “where they will not be served again, they will be preserved,” he said.

Other federal agencies such as the Department of the Treasury and the Government Printing Office are sending books and documents through the Library of Congress scanning center (PDF, 90KB). It’s “an opportunity to demonstrate government transparency,” Kahle said.

The Internet Archive tracks downloads. “It’s great to know that a Library book has now been used dozens or hundreds of times via the Internet Archive,” Handy said. “More funding will be sought to keep this going after this year. This is just the beginning.” (America.gov)

Makes one think of the Alexandria Library of ancient historical fame. Now to preserve our electricity sources and resources so we can continue into the electronic age; I think that’s the next huge problem that needs to be addressed.