A decades-old fusion reactor project in England recently broke its own record for highest-ever sustained energy from fusing atoms together.

Providing just over 11 megawatts of energy over a five-second period using the same process as what powers our Sun, the researchers have laid a foundation for far bigger achievements in the future.

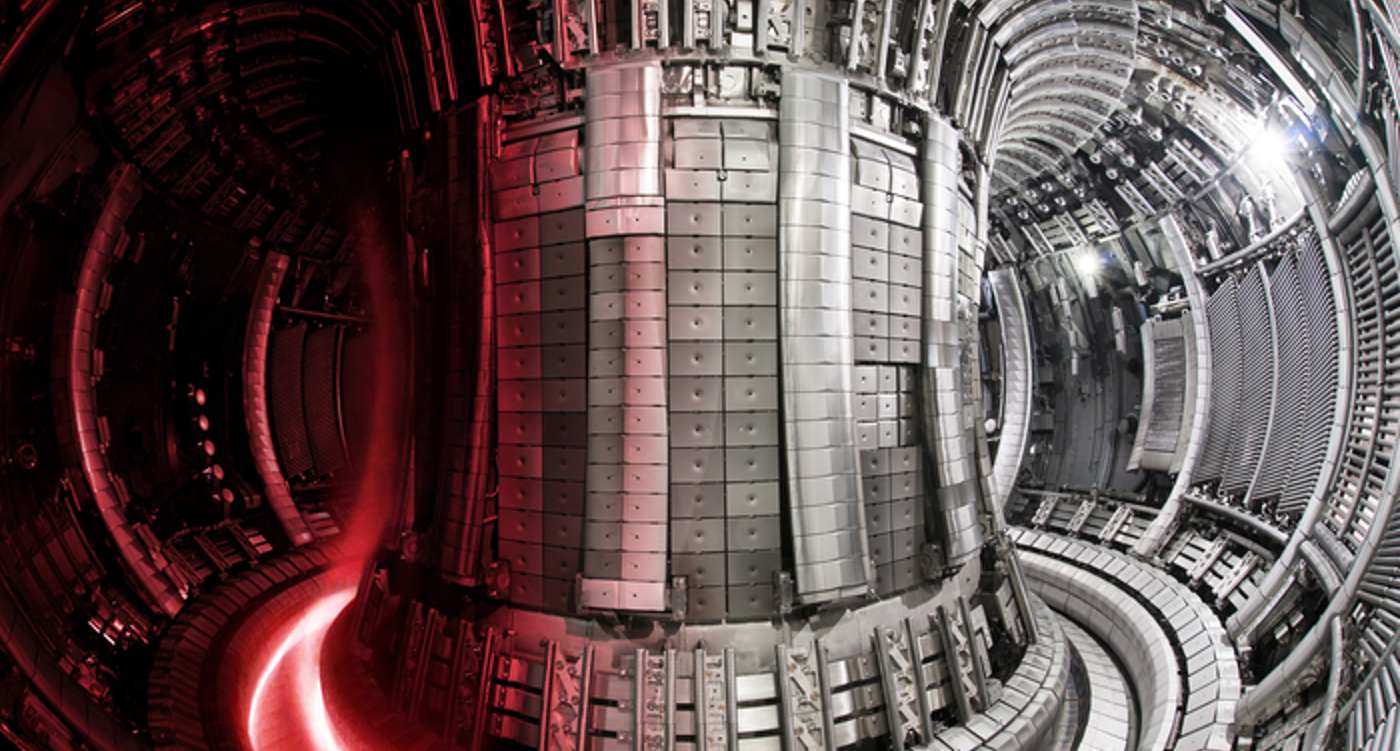

The Joint European Torus (JET) tokamak in Oxford, UK, created a spinning plasma controlled by superconducting magnets which fused hydrogen isotopes together into helium. The neutrons given off as energy during this process generated 59 megajoules of energy, around twice as much as what JET produced the last time it ran this experiment in 1997.

“These landmark results have taken us a huge step closer to conquering one of the biggest scientific and engineering challenges of them all,” said Ian Chapman, who leads the Culham Centre for Fusion Energy (CCFE), where JET is based, in a statement.

When the enormous tokamak nuclear reactor ITER comes online in southern France in 2025, it will be the world’s largest fusion reactor—a comically-large conglomeration of the most complicated engineering components costing $22 billion. But before this massive facility begins testing, the much smaller JET will be able to give the data behind this recently-broken record to ITER’s operators to act as a yardstick, since JET is essentially the same machine only smaller.

Nuclear fusion could mean unlimited clean energy for the world if only scientists can create a reactor that creates more power than it uses.

ITER is expected to produce around 10-times as much as it uses. While JET, a one-tenth mock up of ITER, generated only 0.33% electricity where 1% is breakeven, the same modeling that achieved this result states that ITER will work.

ITER will be powered by two hydrogen isotopes called deuterium and tritium. The former is more easily found, and is used along with seawater in other nuclear fusion tests. The latter is rare in nature and usually only obtained through nuclear fission reactors, that is, normal nuclear power plants. The entire world’s supply of tritium is 20 kilograms, reports Science.

The last time these two isotopes were used to create a plasma was the last time JET set a record for energy produced back in 1997.

RELATED: How Scientists are Managing to Trap the World’s Coldest Plasma in a Magnetic Bottle

“JET really achieved what was predicted. The same modeling now says ITER will work,” fusion physicist Josefine Proll at Eindhoven University of Technology, told Nature. Proll, who was not involved in JET’s research, added that a 5-second plasma containment is “really, really impressive.”

“It’s a really, really good sign and I’m excited.”

In December, the US Department of Energy’s National Ignition Facility set a different fusion record, using laser technology to produce the highest recorded fusion power output relative to power input. The burst beat JET’s 1997 record, but the event lasted less than one second and produced just 1.3 megajoules.

POWER UP the Hope—Share This Story Online…