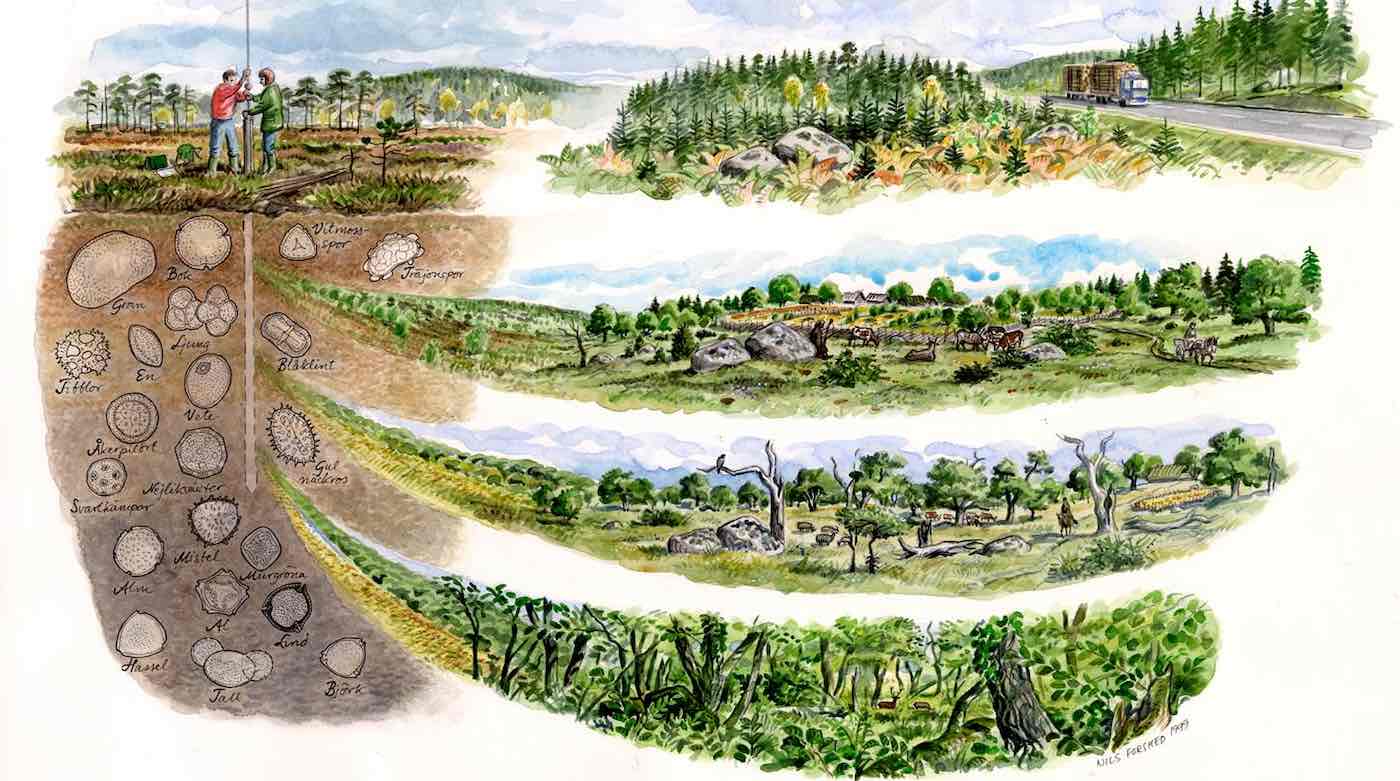

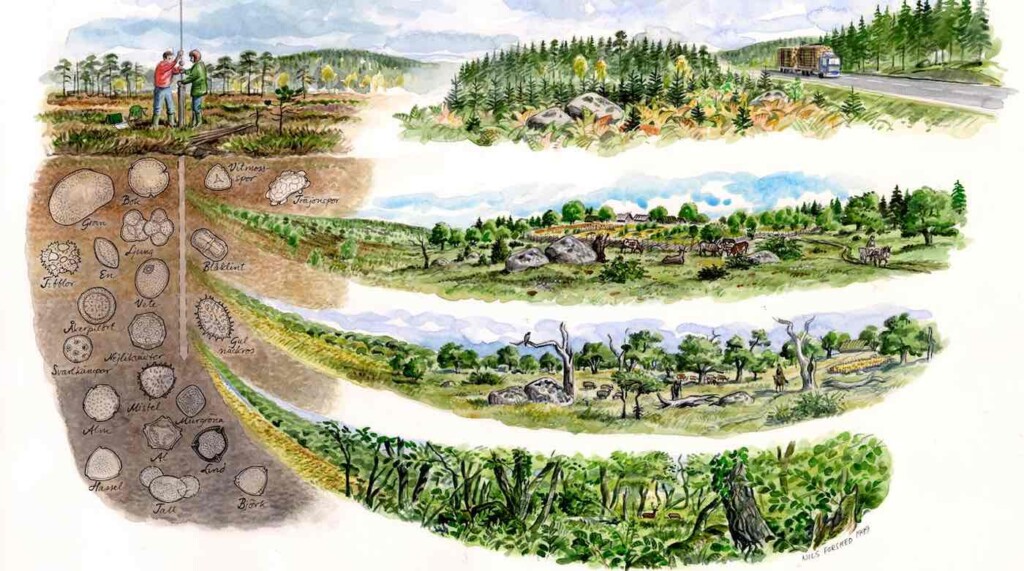

Scientists have devised a method of analyzing preserved hazelnut shells to find out what the habitat was like in prehistoric times.

The Oxford University team note that their research could show not only what a local environment looked like thousands of years ago—whether sites were heavily forested or open and pasture-like—but also how humans may have impacted their habitats over time.

The scientists gathered hazelnuts from trees growing in varying light levels at three locations in southern Sweden, and analyzed their carbon quantities and the relationship between these values and the light levels the trees were exposed to.

They then investigated the carbon values of hazelnut shells from archaeological sites also found in southern Sweden.

They selected shell fragments from four Mesolithic sites and 11 sites ranging from the Neolithic to the Iron Age, some of which had been occupied in more than one period.

The Mesolithic, or middle stone age, ended around 10,000 years ago, the Neolithic was around 6,000 years ago and the Iron Age ended around 2,500 years ago.

The authors note that humans in northern Europe have been using hazel trees as a source of materials and food for thousands of years.

“The nuts are an excellent source of energy and protein, and they can be stored for long periods, consumed whole or ground,” said senior author Dr. Karl Ljung, of Lund University, Sweden. “The shells could also have been used as a fuel.”

LOOK: Family Discovers 8 Huge Dinosaur Footprints While Walking on Eroded Beach

The ratio of carbon dioxide in hazel trees is heavily influenced by sunlight. Where there are fewer other trees to compete for the sunlight and rates of photosynthesis are higher, the hazels will have higher carbon isotope values.

Therefore, based on their analysis of carbon in hazelnut shells the team were able to assign their samples to one of three categories: closed, open, and semi-open.

“This means that a hazelnut shell recovered on an archaeological site provides a record of how open the environment was in which it was collected,” added Dr. Ljung. “This in turn tells us more about the habitats in which people were foraging.”

The study, published in the journal Frontiers in Environmental Archaeology, shows that nuts from the Mesolithic had been collected from more closed environments, while nuts from more recent periods had been collected in more open environments.

By the Iron Age, most of the people who collected the hazelnuts sampled for this study had gathered the nuts from open areas, not woodlands. Their microhabitats had completely changed.

The team hopes to do further research to directly date and measure the carbon isotopes of hazelnut shells from a wider range of sites and settings.

Lead author Dr. Amy Styring, from the University of Oxford said, “Our study has opened up new potential for directly tying environmental changes to people’s foraging activities and reconstructing the microhabitats that they exploited.”

“This will provide much more detailed insight into woodlands and landscapes in the past, which will help archaeologists to better understand the impact of people on their environment.”

SHARE the Nutty News With Ancient History Buffs on Social Media…