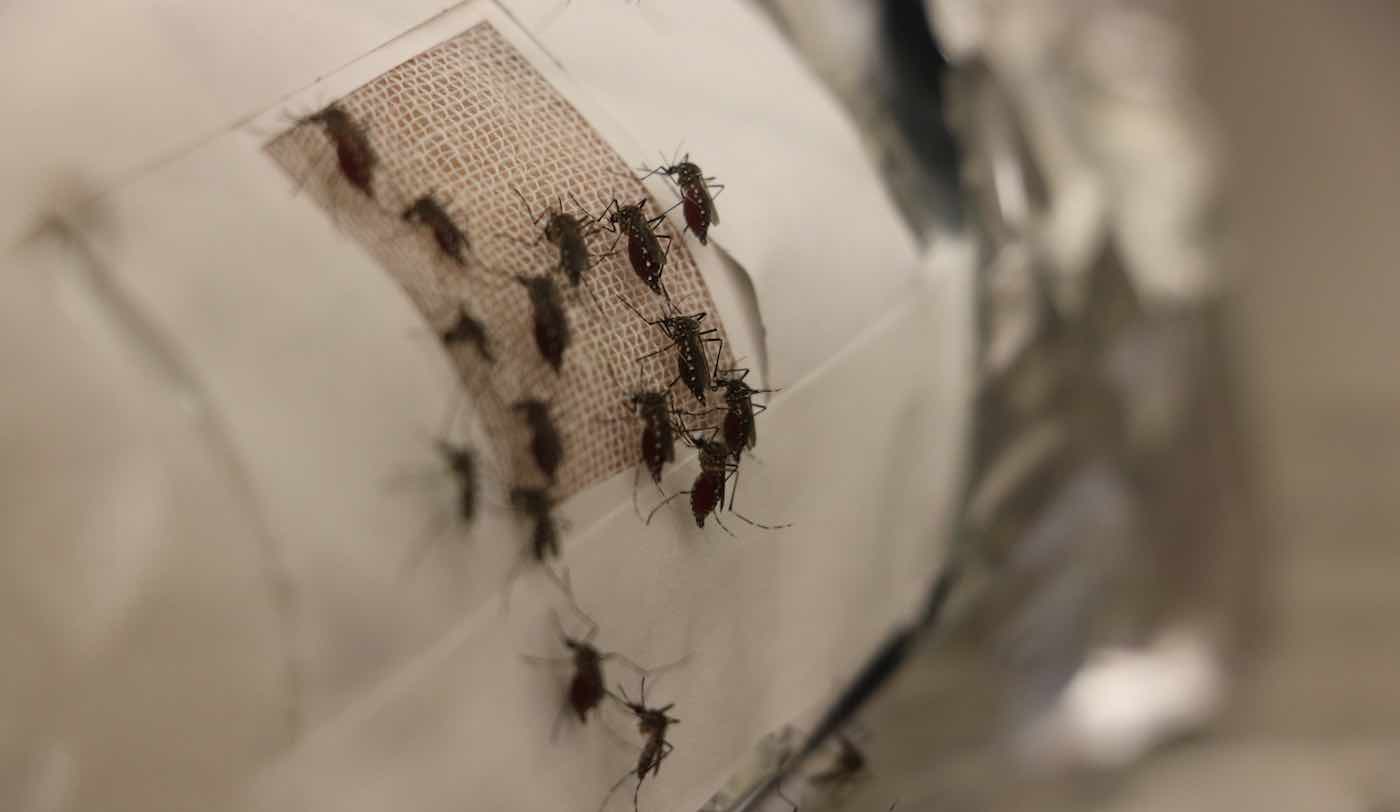

Nearly half the world’s population is at risk for mosquito–transmitted malaria, which actually killed nearly 445,000 people in 2016.

Now, researchers have come up with a way to drastically reduce the frequency of mosquito bites through the use of graphene-lined clothing, which would help stop the spread of deadly diseases like malaria.

The scientists from Brown University discovered that the super-thin and incredibly strong material blocks the odors of sweat which compel the blood-sucking insects to bite.

While also incorporating breathability into the fabric, testing revealed that the material is also too strong for mosquitoes to bite through.

“There’s a lot of interest in non-chemical mosquito bite protection,” said the study’s senior author Professor Robert Hurt who is leading the clothing’s development team.

“We had been working on fabrics that incorporate graphene as a barrier against toxic chemicals—and we started thinking about what else the approach might be good for. We thought maybe graphene could provide mosquito bite protection as well.”

His research team compared the number of bites that participants received on their bare skin, compared to volunteers who had their skin covered in cheesecloth and on skin covered by graphene oxide (GO) films sheathed in cheesecloth.

The researchers were surprised to discover that the mosquitoes completely changed their behavior in the presence of the graphene-covered arm.

Study author Cintia Castilho, a Ph.D. student at the university in Rhode Island, said: “With the graphene, the mosquitoes weren’t even landing on the skin patch—they just didn’t seem to care.

“We had assumed that graphene would be a physical barrier to biting, through puncture-resistance, but when we saw these experiments we started to think that it was also a chemical barrier that prevents mosquitoes from sensing that someone is there.”

The researchers found mosquitoes flocked to areas of graphene barrier dabbed with some human sweat, which confirmed it worked as a chemical barrier. Further tests showed GO was puncture-resistant to mosquito bites, but only when it was dry.

Another form of GO with reduced oxygen content called rGO was shown to provide a bite barrier while it was both wet and dry, but since it wasn’t particularly breathable, the researchers are now trying to find a way to stabilize the GO so that it’s tougher when wet.

“GO is breathable, meaning you can sweat through it, while rGO isn’t,” said Hurt. “So our preferred embodiment of this technology would be to find a way to stabilize GO mechanically so that is remains strong when wet.

“This next step would give us the full benefits of breathability and bite protection.”

The findings were published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Spread The Good News Amongst Your Friends By Sharing This To Social Media…