An Assyriologist from Ireland believes he has discovered the meaning behind a series of symbols always presented together on the walls of the ancient Assyrian city of King Sargon II.

His belief is that rather than being simple motifs or allegorical pieces, they were a way to imprint Sargon’s name in the stars themselves through language, ensuring it would live on forever.

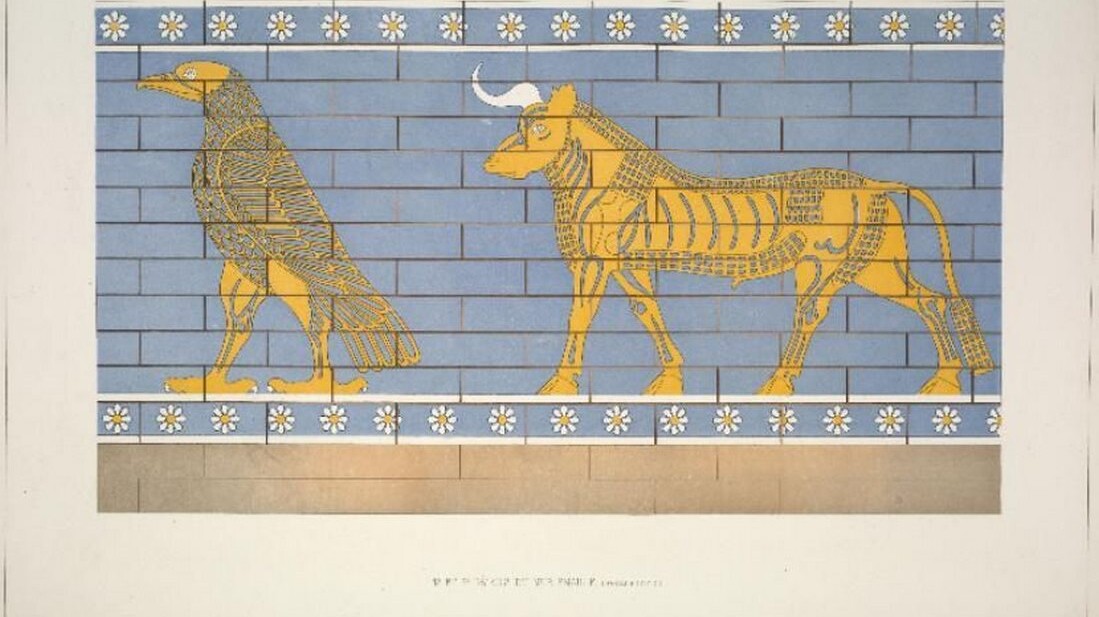

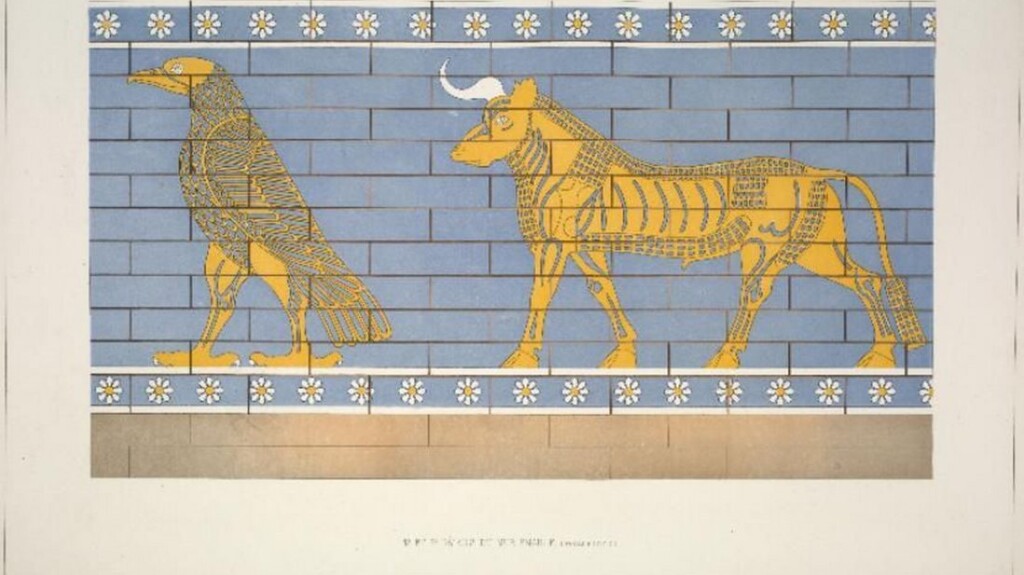

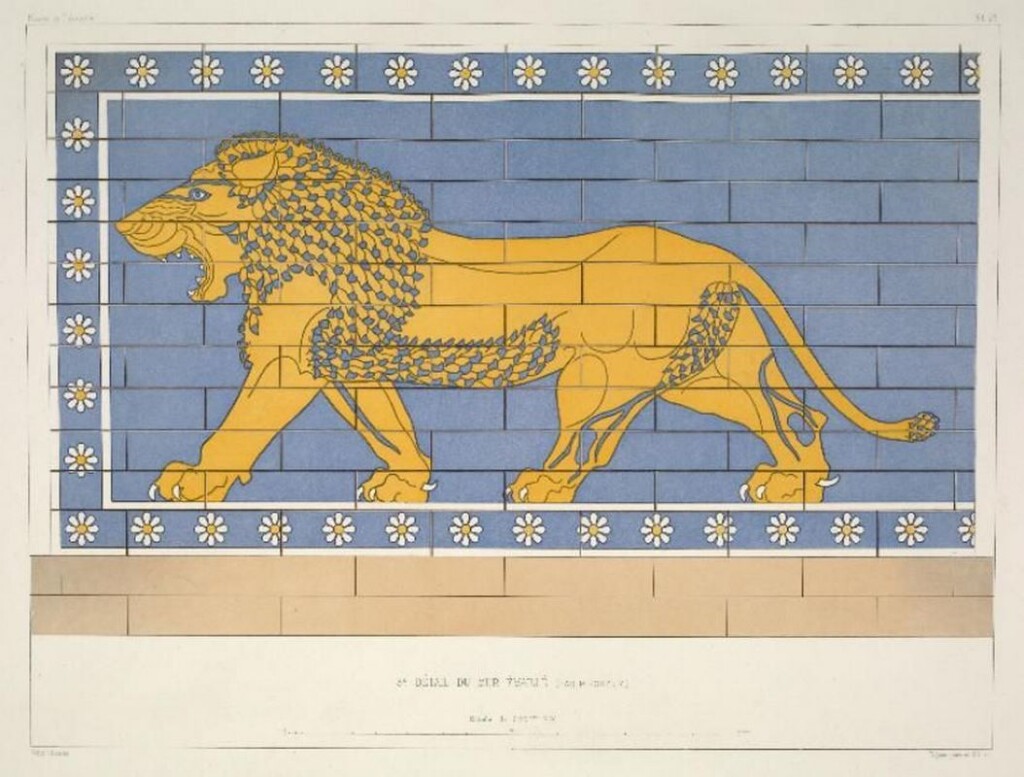

The ancient one-time capital city of Dūr-Šarrukīn, in modern day Iraq, contained multiple instances of a sequence of five images or symbols (lion, bird, bull, tree, plow) which also appeared shortened to three (lion, tree, plow) carved and painted onto the walls of the palace. There is currently no consensus on their meaning.

Animal reliefs are nothing new in Mesopotamian carvings, but in paintings commissioned by French excavators working in the 19th century, we see they were always in the same order.

Dr. Martin Worthington of Trinity College Dublin’s School of Languages, Literatures, and Cultural Studies, proposes a new idea: the words for each animal and object when read together in the order they are depicted more or less sound out the name of Sargon, or šargīnu, as they would have said it back then.

But the clever part is, each of the symbols corresponded to one of the constellations. Trinity College Dublin news reports that the Greeks adopted most of their understanding about the cosmos from Babylon, which the Assyrians also did. We today in turn adopted them mostly from the Greeks, so in Dūr-Šarrukīn we have the lion (Leo) bird (Aquila) bull (Taurus), and the plow (the big dipper).

The only one we don’t recognize on star charts today is the fig tree, but Dr. Worthington decoded that too: it stands in for the hard-to-illustrate constellation ‘the Jaw’ (which we don’t have today), on the basis that iṣu ‘tree’ sounds similar to isu ‘jaw’.

“The effect of the five symbols was to place Sargon’s name in the heavens, for all eternity – a clever way to make the king’s name immortal. And, of course, the idea of bombastic individuals writing their name on buildings is not unique to ancient Assyria,” said Dr. Worthington.

The paper was published in the Bulletin of the American School of Oriental Research.

MORE ANCIENT DECODING:

Most of the time, Assyriologists, or people who study the ancient civilizations of Mesopotamia, are working on transcribing the various cuneiform scripts of tablets found during excavations in the 19th and 20th centuries, of which there are tens of thousands in museum collections that haven’t ever been read.

ANCIENT ARCHAEOLOGY:

“I can’t prove my theory, but the fact it works for both the five-symbol sequence and the three-symbol sequence, and that the symbols can also be understood as culturally appropriate constellations, strikes me as highly suggestive. The odds against it all being happenstance are—forgive the pun—astronomical.”

SHARE This Sharp Professor’s Discovery Solving Of An Ancient Riddle…