In the 1970s and 80s, Costa Rica had the highest deforestation rates in Latin America—but the next few decades saw the country halt her forest loss, initiate replanting and conservation efforts, and regrow almost all of her lost tree cover.

Their methods have set up the most successful forest management model on earth.

Leading the way in the fight against human-accelerated climate change, Costa Rica’s success story of sustainable forestry was strengthened by a simple strategy of valuing forests by paying for their restoration, through their Payment for Environmental Service (PES).

In the 1940s, 75% of the country was shrouded in rainforest, cloud forest, and mangrove. But over the next 40 years, it is estimated that as much as half of all the trees were cut down. Intense logging bans were instituted in 1996, with PES programs arriving the year after.

Harnessing the indefatigable forces of economics, PES conservation strategies mean the forest is essentially treated like a utilities company, with companies or beneficiaries of the resources and processes provided by the forest, ‘paying’ the forest for the service or resource.

For example, a stand of old trees sit on a farmer’s acre who knows he could chop them down and plant cacao, coffee, bananas, or other tropical agriculture products. Instead he receives money from a fund which businesses and citizens pay into so that he can afford to keep the forest intact.

Now 60% of the country is forested once again, and every year, the Costa Rican Forest Fund collects $33 million which it uses to make sure the forests of Costa Rica which sit on privately-owned land are taken care of. $500 million has been paid out to landowners and farmers over the last 20 years, stewarding 2.4 million acres (1 million hectares) of rainforest, and incentivizing the planting of 7 million new trees.

POPULAR: Indigenous Group in Brazil Wins Decades-Long Battle Against Illegal Loggers in the Amazon

A society in balance with the Earth

“People in Costa Rica receive a lot of money because of tourism and that changes the incentives of land use,” Juan Robalino, an expert in environmental economics from the University of Costa Rica, told CNN.

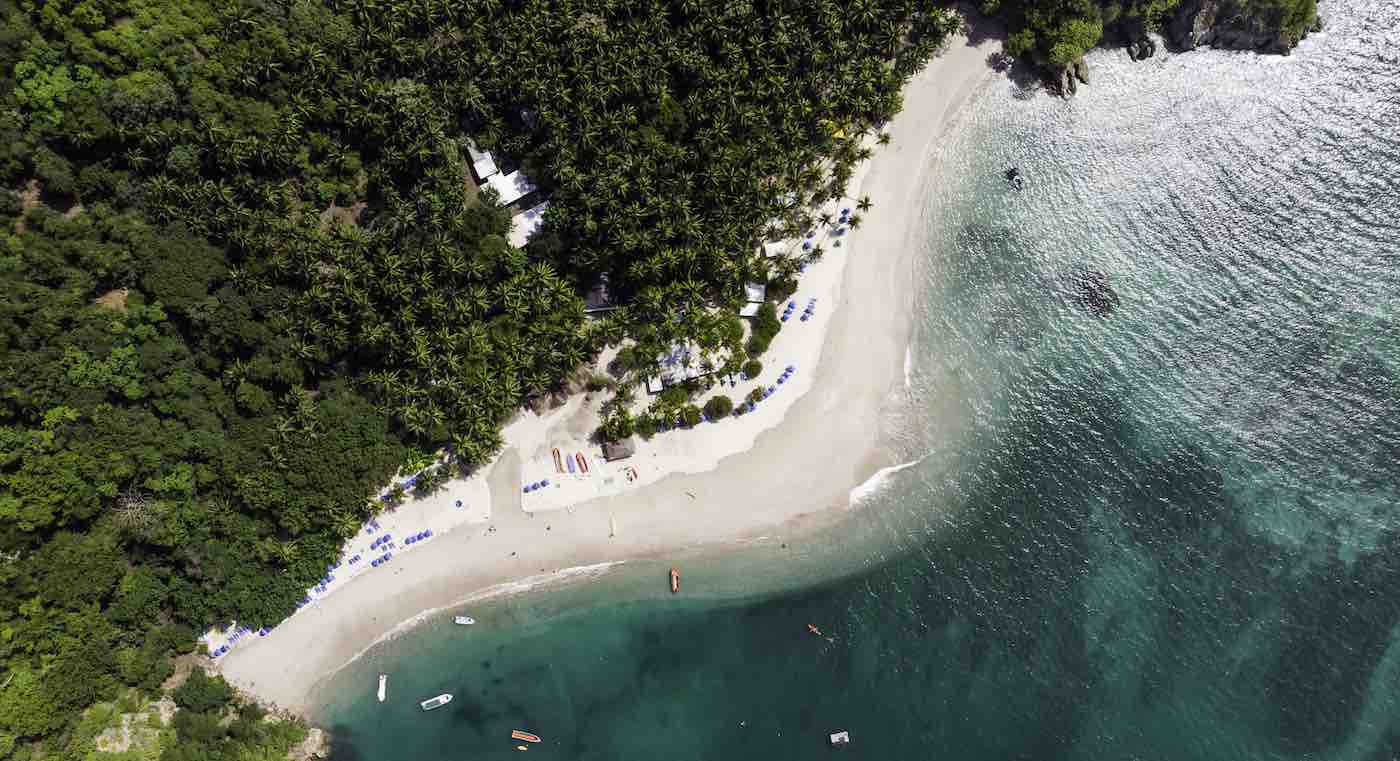

That’s because almost three million tourists come to see the country’s national parks and other protected areas, which cover a quarter of the nation and are home to half a million documented plant and insect species, including iconic animals like the sloth and great green macaws.

Employing 200,000 people, the tourism sector generated $4 billion in revenue last year, encompassing luxury beach-side resorts, and little agro-tourism spots like Pedro Garcia’s farm, who took advantage of the PES opportunity to transform a 7-hectare cattle ranch into a pristine slice of Costa Rican rainforest with native trees and wild agricultural products that provide homes for macaws, poison-dart frogs, and more.

Costa Rica’s PES system has been adopted by other nations across the world in recognition of its success—notably Rwanda, whose commitment to restoring its natural forest ecosystems saw them sign a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with Costa Rica in 2019.

“We’ve been working together for the last 3 years. We look forward to implementing it [MoU] and possibly expanding the scope in the future,” said Rwandan Environmental Minister Biruta at the time.

RELATED: Man Succeeds Where Government Fails: He Planted a Forest in the Middle of a Cold Desert

“We have learned that the pocket is the quickest way to get to the heart,” Carlos Manuel Rodríguez told CNN. As Costa Rica’s Minister for Environment and Energy, Rodríguez understands that while placing a dollar value on the natural world may seem dirty and unethical, it’s the best incentive for people to work to conserve the environment.

GROW Some Hope on Your Social Media Feeds By Sharing This Good News With The World…