By Derek Maiolo

Ten years ago, a clumsy but enthusiastic Great Dane named Walter was out with his owners on public land near Rangely, Colorado, when he stopped near a strange-looking rock.

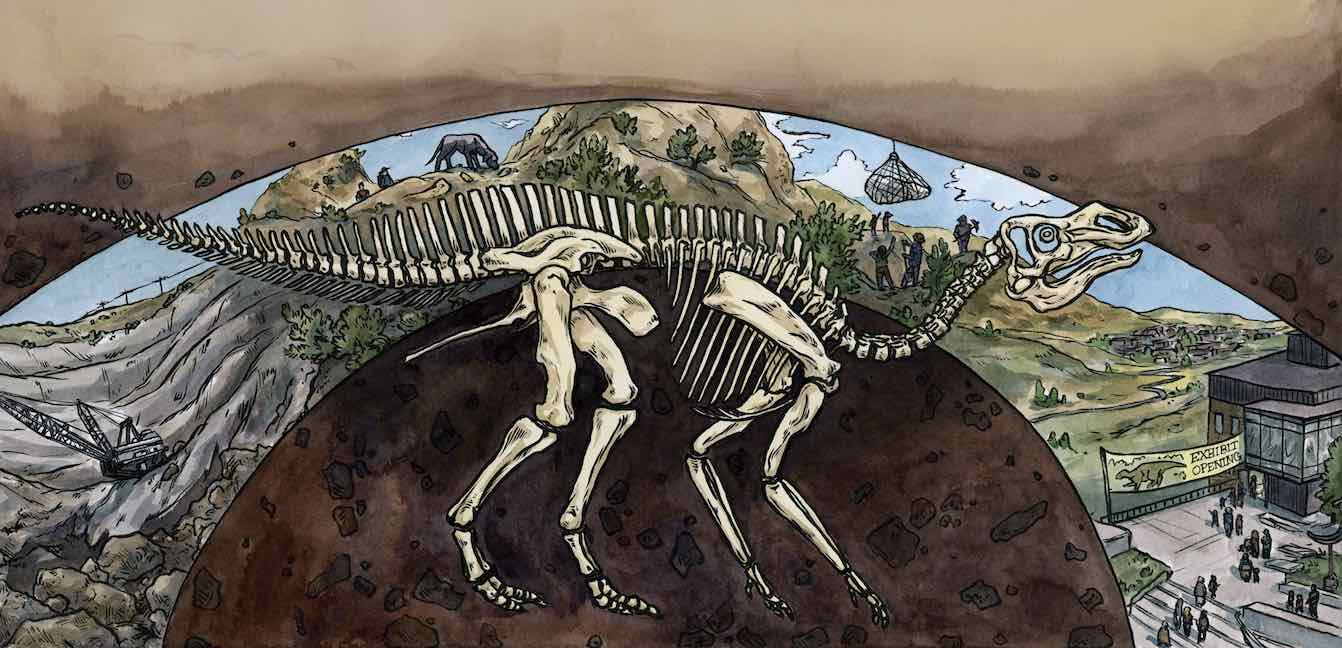

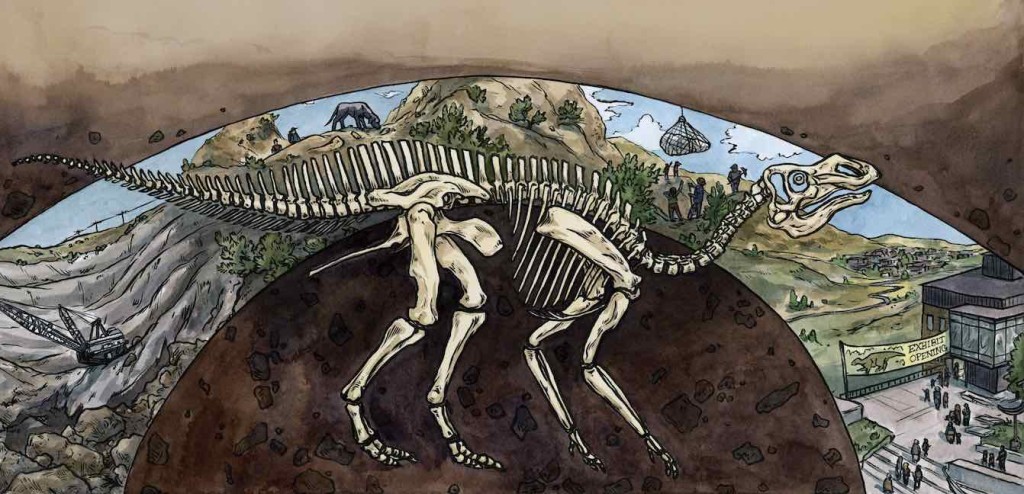

His owners investigated and found what experts say was a 74 million-year-old fossil. After painstaking work, scientists uncovered a nearly complete specimen of a hadrosaur duck-billed dinosaur.

Now, the Cretaceous-era fossil proudly carries the name of its paleontologist pooch: Walter.

The same year Walter was found, Colorado’s coal production hit a 20-year low; the town of Craig’s power plant and coal mines in the county are scheduled to shut down by 2030. Numerous businesses have closed, and Ms. Johnson dreams of turning one of those empty buildings into a dinosaur museum to attract tourists.

Rewind time just a bit, and it was near the cypresses and ferns of a brackish swamp that an aging dinosaur strained its arthritic body to drink. It was about as long as a school bus, with a bony lump on its nose and an old wound that had become infected.

Perhaps it died there, or maybe it was still lumbering about when a flood or landslide struck and sediment buried its body, along with the surrounding cypress and ferns. Heat and pressure compacted the vegetation into coal. But the dinosaur, encased in a sarcophagus of mud and sand, remained intact.

Hadrosaurs—the “cows of the Cretaceous”—once grazed in herds across prehistoric North America and Eurasia. Walter is a remarkably complete specimen, and researchers believe that this fossil represents a new species.

As the scientists, volunteers, and students excavated, they found more fossils: a Daspletosaurus tooth, chunks of what may be dinosaur skin, and imprints of ancient plants like screen prints on the rock. The Paleontological Resources Preservation Act says that such discoveries must go to approved repositories, typically at government or museum facilities in cities like Denver and Washington, D.C.

MORE DINOSAUR NEWS: ‘Impossible Fossil’ Preserves the Exact Moment the Dinosaurs Died: ‘It’s Absolutely Bonkers’

But Liz Johnson, a paleontologist at Colorado Northwestern Community College, wanted to change that.

“This is northwest Colorado history. It should stay in northwest Colorado,” she said. Fortunately, that was also in the federal government’s interest, so the Bureau of Land Management worked with the college to make it happen, short-circuiting a process that can take years, if not decades. Walter and the other finds will stay in Craig.

MORE FOSSIL NEWS: Long Before Trees Overtook the Land, Our Planet Was Covered by Giant Mushrooms

The town of Craig loves Walter; the county visitor center sells replicas of Walter’s tooth. Students and community volunteers worked for five summers to help uncover Walter’s remains. The most dedicated volunteers still spend weekends and holidays meticulously cleaning fossils.

In 2021, visitors to Dinosaur National Monument, about a hundred miles to the west, spent $24.3 million. That’s a lot of money, but tourism doesn’t pay as well as mining. Still, as Craig scrambles to attract investors and new industries, Walter’s fans hope paleo-tourism can add fresh appeal. “This place used to be a swamp. Now it’s high desert. Change is constant,” Johnson said. “We have to change, too.”

SHARE This Small Town Story With Your Friends On Social Media…