The terrific cost of World War II, both human and financial, forced England to consider sending away thousands of its children to live in the far reaches of its empire, even ripping them from homes and families to do so. One such child experienced a happy ending, after the lad, now a man, returned from New Zealand to find his boyhood home and reunite with a mum who’d grieved over him for years.

The terrific cost of World War II, both human and financial, forced England to consider sending away thousands of its children to live in the far reaches of its empire, even ripping them from homes and families to do so. One such child experienced a happy ending, after the lad, now a man, returned from New Zealand to find his boyhood home and reunite with a mum who’d grieved over him for years.

Anthony (Tony) Chambers says he was one of the lucky ones. In a story written for the Good News Network, Tony recalled his happy life in New Zealand and his return, full circle, to the town where he was born and into his mother’s life once agin.

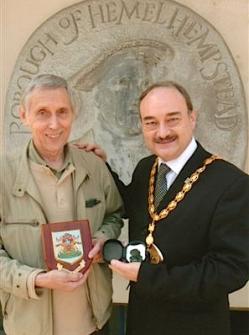

Photo: Tony Chambers, left, presented with the coat of arms of Hemel Hempstead, and giving the mayor of his birth town a New Zealand “Maori Tiki” good luck charm in return — supplied by Hemel Hempstead Gazette/Victoria West.

(WATCH the moving short documentary following Tony’s story)

My original migration as a nine-year old British boy is a story not well known in the United States. We child migrants are a living part of an old British Empire and its Commonwealth history.

I was born in England but not bred there; fate had me raised as a happy New Zealander. But this was not the case for so many former child migrants scattered around world shipped off to live in host countries. Many went into sad circumstances. A few had reasonable lives, even fewer had the wonderful opportunity that was given to myself.

Yet why did our birth country ship us away? This saga started before the first World War, even. Up to a 150,000 were packed off to Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Southern Rhodesia, South Africa, odd other places where the British held sway.

The fact was, we were displaced family, children from broken homes, or families effected socially by post-war hardship. But we were not child war evacuee’s; they were cherished by their country and given return tickets, while we were sent away with one-way tickets and no hope for return.

It may have seemed a good thing to do in those days. Britain at the time ruled a good portion of the world and promoted the idealism of a new colonial way of life away from stressed-out Britain.

Things were tough in 1951 before I was shipped to New Zealand, but we were not at war. Many potential child migrants lived in orphanages or care homes. Many never knew a mother or father or family member.

Things were tough in 1951 before I was shipped to New Zealand, but we were not at war. Many potential child migrants lived in orphanages or care homes. Many never knew a mother or father or family member.

But I had a family, although we were poor and being raised by a single mother who needed to work. Many disadvantaged parents thought their children were going to be raised on home soil — and believed the separation would be temporary. My mother had been advised to send me away to what she misunderstood was going to be a reasonable time period of better care, up-bringing and education. Little be-known to her she also was a victim of the British child migration policies.

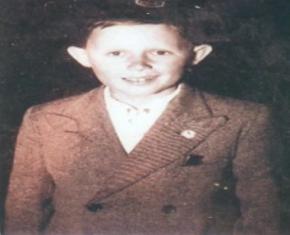

I was nine years old in December of 1951 when I sailed away from London. My mother whom I loved, the only home I knew, the little town I had been born into, all left behind. I was going someplace, but not knowing why. My mother would go on to live a saddened nightmare for her misunderstanding.

I was put up for adoption and went into a kind & loving home. Growing up with a good New Zealand life brings me to the “Good news” part of the story.

I loved my new parents and extended adoptive family, they loved me. I gained a good basic education, and later, a printing engineering trade background. Yet I still decided at the age of 22 to return to Britain of my own financial accord to search for my lost birth roots.

After much land and sea travelling I located, by memory, my old birth town & mother. I only stayed a year. New Zealand was my new home. I married my new Spanish wife, Maria, in London and returned home, later raising two sons born in the country I had come to love. As an added bonus, I embraced extended family heritage and twin countries in both Australia & Spain.

Now, in my retirement years, after much emigrational travel, I did come back with my wife to Europe. I cared for my birth mother in her final years, while still holding NZ very dear.

The short film, Boy in the Lifebouy documents the return of a British child migrant from New Zealand. The filmmaker, Sejal Deshpande, received her Masters in Televion and Interactive Content, is currently Freelancing for British Asia TV and the Sikh Channel, while working on a another documentary. She currently resides in England.