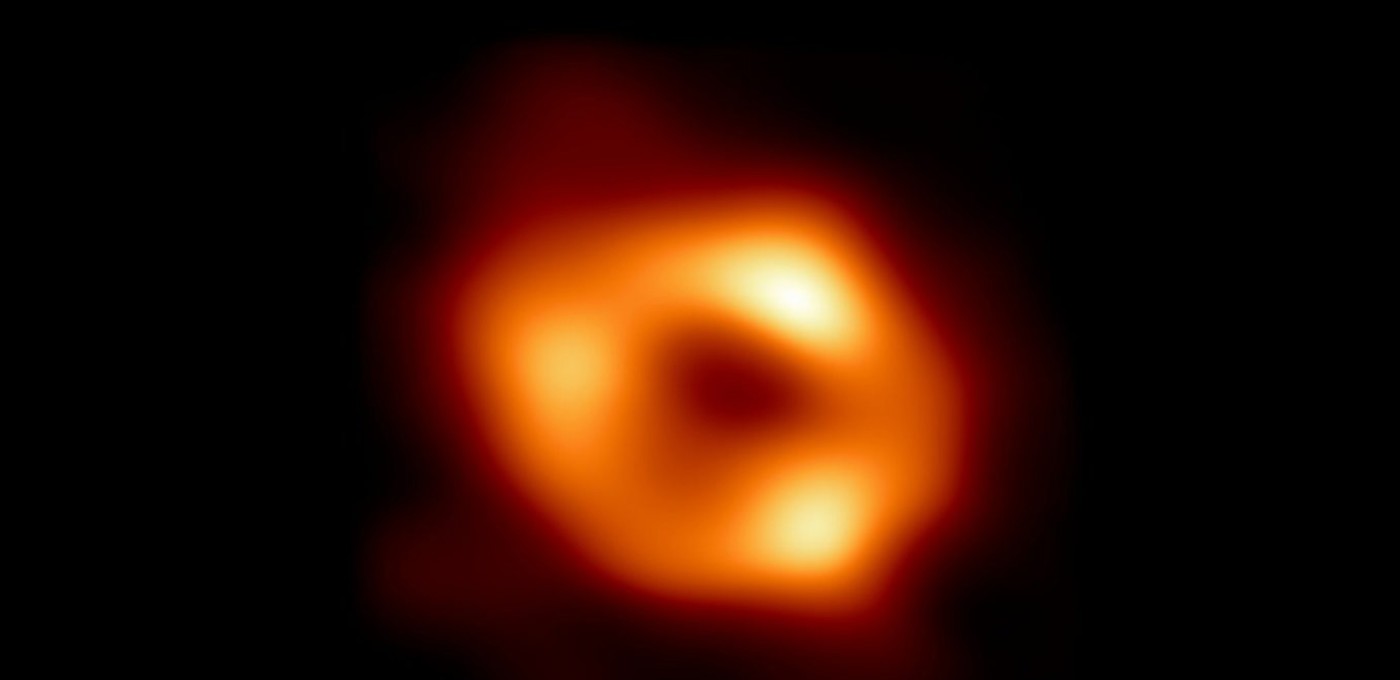

The gargantuan black hole which binds our galaxy together with its powerful gravity has been imaged for the first time.

The capture relied on the collaboration of telescopes from all over the world acting in sync, collecting several millions of gigabytes of data to present the burning accretion disk of Sagittarius A—our black hole’s official name.

How can one image a phenomenon that sucks in light? Something that’s invisible and that we can only picture because of artists’ interpretations? A black hole’s gravitational pull is constantly pulling in, and actually belching out, hot gases and radiation, which form something known as the accretion disk.

This vortex of extremely hot energetic material swirling into the black hole betrays its presence, in the same way that throwing a pound of flour onto an invisible man would reveal them.

The photograph was a project of the Event Horizon Telescope network (EHT), which won Science Magazine’s photo of the year in 2019 for their first-ever image of a black hole called Messier 87. Readers may remember that, just before the pandemic, a glowing orange ring on a black field appeared on the front page of virtually every news outlet.

MORE: This is What it Looks Like When a Black Hole Snacks on a Star

“But this new image is special because it’s our supermassive black hole,” said Prof. Heino Falcke, who also led the European team behind the imaging of M87. “This is in ‘our backyard’, and if you want to understand black holes and how they work, this is the one that will tell you because we see it in intricate detail,” the German-Dutch scientist from Radboud University Nijmegen told BBC News.

But how?

At 26,000 light years away, Sagittarius A is four million times larger than our Sun, and the event horizon, the part of space around a black hole where the laws of physics begin to break down in relation to its presence, is about as wide as Mercury’s orbit around the Sun, or around 40 million miles across.

RELATED: Have We Detected Dark Energy? Cambridge Scientists Say It’s a Possibility

One aspect of the discovery that’s almost as difficult to wrap one’s head around as the measurements above, is that all the images used to construct the finished product of Sag. A were taken during the same observation period that gave us the Messier 87 image.

However, since Messier is in a neighboring galaxy, the distance the light traveled to arrive here makes it appear static, while the proximity of Sag. A meant that the plasma in the accretion disk, moving as it does at about 190,000 miles per second, was much harder to piece together into a concise image.

CHECK OUT: Astronomers Capture Black Hole Eruption Spanning 16 Times the Full Moon in the Sky

Because Sag A. is a thousand times smaller than M87, the structure of its disk changes a thousand times faster, which combined with the reduced time the light needed to arrive here meant a much greater challenge creating an image that wasn’t just a single orange blur.

The brighter parts of the image are thought to be where radiation is coming right towards us.

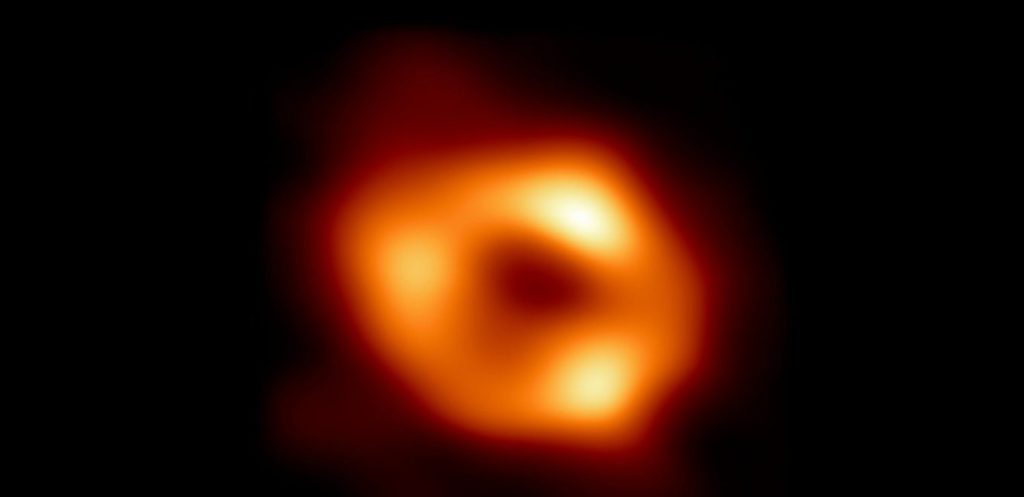

Below, the scientists created a simulation of what you might see if you traveled to the center of the galaxy and looked at Sag. A through an optical tool that caught sensitive radio frequencies.

(WATCH the video for this story below.)

SHARE a Cosmic Spiral of the Good News; Share This Story…