50 years worth of conserving the tern and puffin populations in Maine has created a stable colony of thousands of breeding birds.

Located on Petit Manan and other small islands off the coast, the birds have absorbed the worst of climate change during the 2000s, and are returning just as before to large numbers of breeding pairs and fledgling chicks.

Even the wildest gambler wouldn’t have put a penny on the Atlantic puffins of Maine making it out of the 20th century alive, after they were hunted down to just 2 birds by 1902.

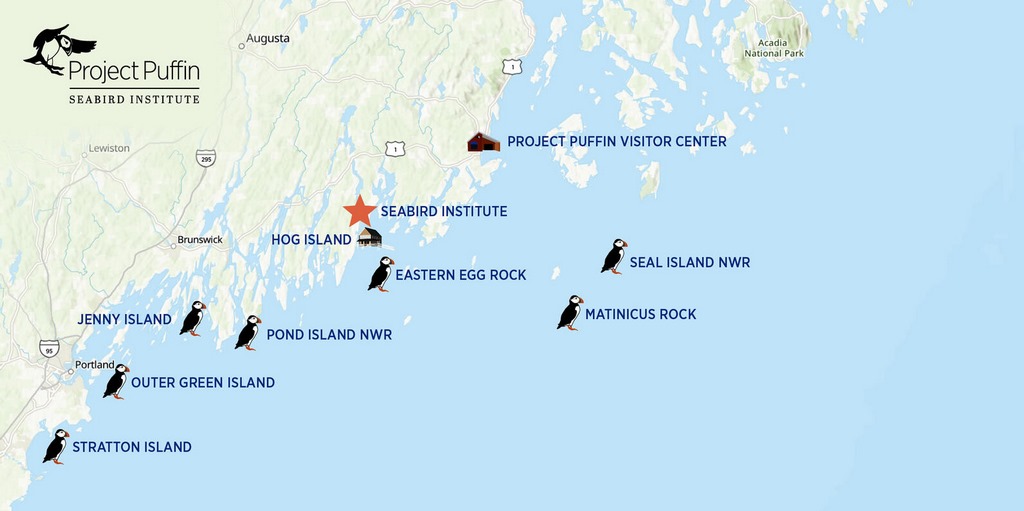

Huddled on Matinicus Rock, the remotest spit of land in what today is the Maine Coastal Islands National Wildlife Refuge, an Audubon Society member began bringing down puffin chicks from Newfoundland in 1972 to try and recreate their breeding booms that would cover every square inch of rock in squawking chicks a century earlier.

Today there are more than 1,300 pairs of puffins across several islands, mostly on Eastern Egg Rock, Seal Island, and Matinicus Rock. The project was the first one in history that restored a seabird to an offshore island where it had been extirpated by humans.

On Petit Manan, another of the islands, the arrival of puffins was a happy accident. The more native bird has also faced dire plights.

Common, Arctic, and roseate terns sheltered on the island in their thousands. Then a lighthouse manned for decades by the U.S. Coast Guard was, in the late 1970s, automated. This abandonment caused an imbalance in the number of gulls that kept nests there.

This imbalance was corrected in the 80s after the terns all but left the island entirely, and the terns return. By the turn of the millennia there were 2,500 breeding pairs.

It seemed that these delicate coastal bird sanctuaries were in the clear, but warming waters and shorter springs, winters, and autumns began devastating the populations as the cold water fish species the puffins and terns preyed on stayed further out to sea.

RELATED: Island is Wonderland for Penguins Once Again After Dog Helps Eradicate 300,000 Invasive Rabbits

Harsher sun damaged the cold and wet-loving native plant life, and nests became harder and harder to build.

A number of students and conservationists that make up Project Puffin, an Audubon Society success story that watches over the Maine islands, have been blown away by the resilience of these birds.

In 2009 the puffin breeding pairs fell to a bleak 47, while only 16% of all tern chicks reached adolescence.

Using leg bands, the teams at Project Puffin keep track of birds they capture and release for research. Return of cooler weather over the years has meant they’re finding more and more chicks reaching adulthood, more and more adults settling down to breed, and some migrating terns racking up a speech-stealing 2.3 million migratory miles.

One puffin was found to have reached 35 years of age.

“When you hold a bird that travels like it does and it looks into your eyes and you look into its eyes, I constantly wonder what is going on it its mind,” Kaiulani Sund, a 21-year-old senior at Gettysburg College, told Environmental Health News.

READ MORE: Birdwatchers Flock to See Rare 8-ft Raptor After Huge Russian Eagle Takes Detour into Maine

Project Puffin gets incredibly anxious around spring hatching season since the difference between a normal year and a bad year in terms of temperatures and food availability can be so impactful on these delicate and wonderful avians. But they soldier on, building artificial puffin burrows, introducing more students from more schools to the project, and hoping for cooler winters.

TWEET On Social Media About This Squawking-Great News…