An African psychedelic plant “significantly” alleviated the symptoms of war veterans suffering from traumatic brain injuries (TBIs), according to another new study.

Ibogaine, a naturally occurring compound found in the roots of the African shrub iboga, was found to successfully improve functioning, PTSD, depression and anxiety in military veterans.

The plant-based psychoactive drug, which has been used in Africa for a thousand years during spiritual and healing rituals, was also found to contain no adverse side effects—with some veterans saying the experimental treatment saved their lives.

Hundreds of thousands of troops serving in Afghanistan and Iraq have sustained TBIs in recent decades, and these injuries are suspected of playing a role in the high rates of depression and suicide seen among military veterans. With mainstream treatment options not fully effective for all veterans, researchers have sought therapeutic alternatives.

Ibogaine has gained notoriety in scientific communities for its potential to treat opioid and cocaine addiction, because it increases signaling of several important molecules within the brain, some of which have been linked to drug addiction and depression.

Traumatic brain injury is defined as a disruption in the normal functioning of the brain resulting from external forces—such as explosions, vehicle collisions or other bodily impacts. Such trauma can lead to changes in the structure of the brain, which, in turn, contributes to neuro-psychiatric symptoms.

Stanford Medicine researchers discovered that ibogaine, when combined with magnesium to protect the heart, safely and effectively reduces symptoms like PTSD, anxiety, and depression—and improves functioning—in veterans with TBI.

Their new study, published on Jan. 5 in Nature Medicine, includes detailed data on 30 veterans of U.S. special forces.

“No other drug has ever been able to alleviate the functional and neuropsychiatric symptoms of traumatic brain injury,” said Nolan Williams, MD, an associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences. “The results are dramatic, and we intend to study this compound further.”

Since 1970 ibogaine has been designated as a Schedule I drug, preventing its use within the U.S., but clinics in both Canada and Mexico offer legal ibogaine treatments.

“There were a handful of veterans who had gone to this clinic in Mexico and were reporting anecdotally that they had great improvements in all kinds of areas of their lives after taking ibogaine,” Williams told Stanford Medicine News. “Our goal was to characterize those improvements with structured clinical and neurobiological assessments.”

MORE BENEFITS: People Who’ve Tried Psychedelics Have Lower Risk of Heart Disease and Diabetes

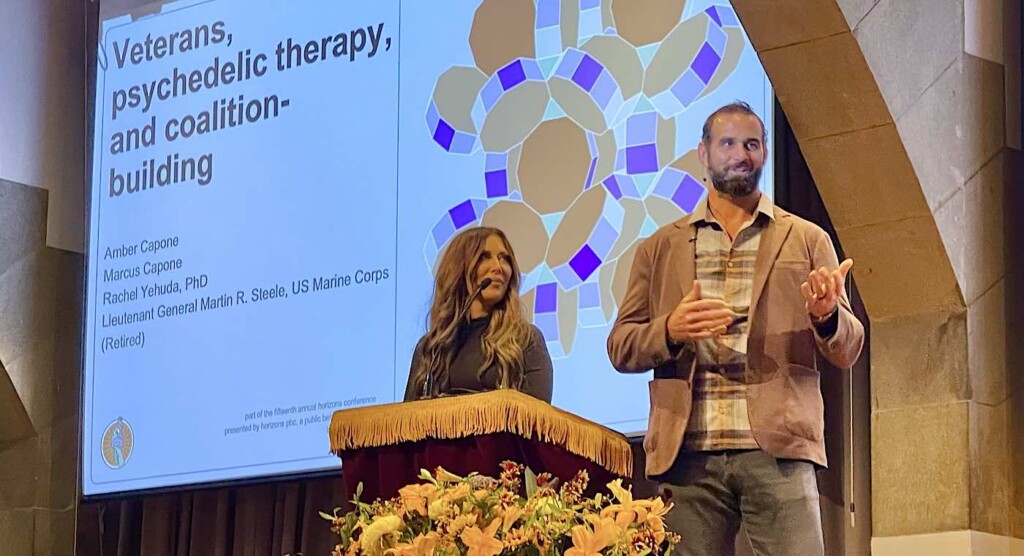

Dr. Williams and his Stanford team partnered with VETS, Inc., a foundation that has facilitated psychedelic-assisted therapies for hundreds of veterans. 30 special operations veterans with a history of TBI and repeated blast exposures—almost all of whom were experiencing clinically severe psychiatric symptoms and functional disabilities—were recruited after they’d independently scheduled themselves for an ibogaine treatment at a Mexico clinic.

Before the treatment, the researchers gauged the participants’ levels of PTSD, anxiety, depression and functioning based on a combination of self-reported questionnaires and clinician-administered assessments. Participants then traveled to a clinic in Mexico run by Ambio Life Sciences, where under medical monitoring they received oral ibogaine along with magnesium to help prevent heart complications that have been associated with ibogaine. The veterans then returned to Stanford Medicine for post-treatment assessments.

19 of the participants had been suicidal, and seven had attempted suicide.

“These men were incredibly intelligent, high-performing individuals who experienced life-altering functional disability from TBI during their time in combat,” Williams said. “They were all willing to try most anything that they thought might help them get their lives back.”

On average, treatment with ibogaine immediately led to significant improvements in functioning, PTSD, depression, and anxiety. Moreover, those effects were still lasting one month after treatment, when the study ended.

Before treatment, the veterans had an average disability rating of 30.2 on the disability assessment scale, equivalent to mild to moderate disability. One month after treatment, that rating improved to 5.1, indicating no disability.

Similarly, one month later, they experienced average reductions of 88% in PTSD symptoms, 87% in depression symptoms and 81% in anxiety symptoms. Formal cognitive testing also revealed improvements in participants’ concentration, information processing, memory and impulsivity.

“I wasn’t willing to admit I was dealing with any TBI challenges. I just thought I’d had my bell rung a few times—until the day I forgot my wife’s name,” said Craig, a 52-year-old study participant from Colorado who served 27 years in the U.S. Navy.

“Since [ibogaine treatment], my cognitive function has been fully restored. This has resulted in advancement at work and vastly improved my ability to talk to my children and wife.”

“Before the treatment, I was living life in a blizzard with zero visibility and a cold, hopeless, listless feeling,” said Sean, a 51-year-old veteran from Arizona with six combat deployments who participated in the study and says ibogaine saved his life. “After ibogaine, the storm lifted.”

MUSHROOM MAGIC: Another Study Shows Psychedelic Psilocybin Mushrooms Offering Long-Term Relief From Depressive Symptoms

Importantly, there were no serious side effects of ibogaine and no instances of the heart problems that have occasionally been linked to ibogaine. During treatment, veterans reported only typical symptoms such as headaches and nausea.

The team is planning further studies, along with analysis of brain scans that could help reveal how ibogaine led to improvements in cognition. They also think ibogaine’s drastic effects on TBI suggest that it holds broader therapeutic potential for other neuro-psychiatric conditions.

“I think this may emerge as a broader neuro-rehab drug,” said Williams. “I think it targets a whole host of different brain areas and can help us better understand how to treat other forms of PTSD, anxiety and depression that aren’t necessarily linked to TBI.”

SHARE THE FANTASTIC NEWS With Veterans on Social Media…