In the northern Pacific Ocean, a powerful ocean ‘gyre’ pulls together several ocean currents into a single region—the site of the infamous Great Pacific Garbage Patch (GPGP).

However, longer before there was plastic waste in these waters, and in spite of it, the Northern Pacific ocean gyre is teeming with specially-adapted marine organisms that drift through the sea.

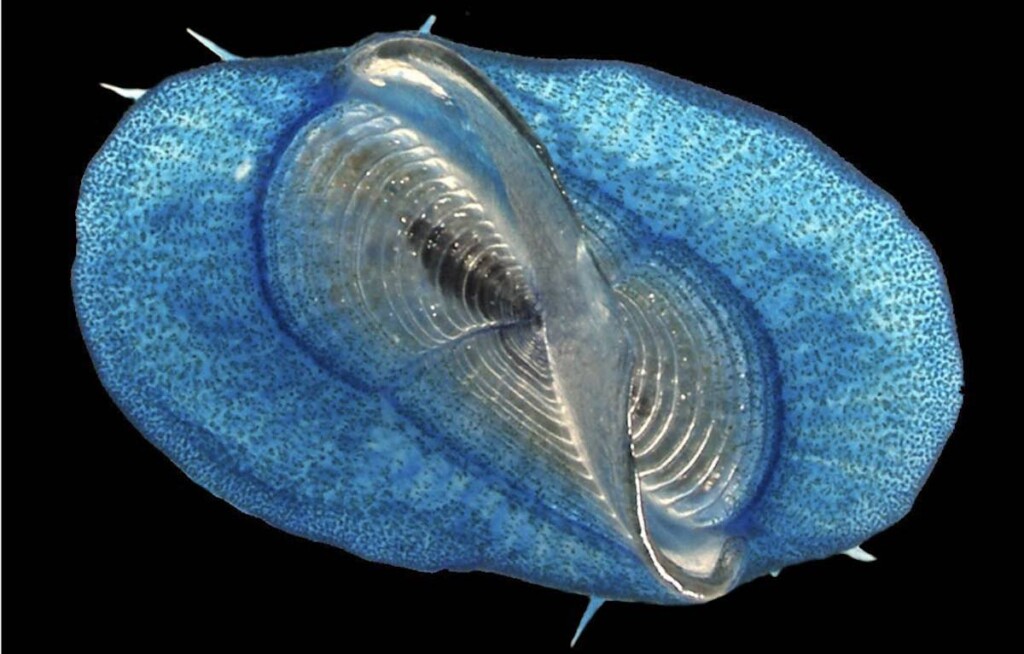

Take this beautiful violet snail above, constructing floating bubble rafts by dipping its body into the air and trapping one bubble at a time, which it then wraps in mucus and sticks to its floater.

Scientists recently documented hundreds of different life forms all concentrated within the center of the GPGP, where 1.8 trillion pieces of plastic have created an environmental feature like no other on Earth.

A swimmer named Benoît Lecomte completed a swim of 389 miles across the GPGP in 2019 and asked the scientists at Georgetown University to accompany the support crew in order to document the sea life.

The work they did has now been published in the journal PLOS One. They found greater concentrations of wildlife inside the GPGP than on its periphery. This is not because of, but in spite of, the trillions of pieces of plastic, as these living ocean hitchhikers evolved to use ocean gyres and currents to get around over thousands of years.

Violet snails, blue button jellies, by-the-wind sailor jellies, and sea slugs called blue sea dragons that hunt the tentacles of man o’ wars to use as makeshift protection, are all found there in large numbers.

“We saw just massive amounts of life at the surface,” study senior author Rebecca Helm, a marine biologist at Georgetown University, told National Geographic. “We’ve seen so many pictures of plastic from the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, but we’ve never seen any pictures of life there.”

“These places that we’ve been calling garbage patches are really important ecosystems that we know very little about.”

MORE SURPRISING OCEAN LIFE: Scientists Discover Pristine Deep-Sea Coral Reefs in Galápagos Marine Reserve ‘Teeming With Life’

The technical term for all this floating sea life is called neuston, and much of it is colored blue atop, and white beneath—a sort of camouflage Helm and her team believe.

Most of our children will never be able to see the GPGP, because it’s currently on track to be totally cleaned down to the microplastic level over the next 20 years.

SHARE This Inspiring Change Of The Narrative With Your Friends…