More than 700,000 objects in the universe are available for study as part of a 3D map cleverly produced by scientists looking to study the effects of dark energy.

Most substance in the universe is either dark matter, an invisible kind of mass that pulls galaxies towards each other and builds structures, or dark energy, an even more mysterious force that causes the expansion and acceleration of the universe.

Scientists at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory are using the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument (DESI) to map more than 40 million galaxies, quasars, and stars in an effort to understand this force’s effect on our reality.

Last week, the collaboration publicly released its first batch of data, with nearly 2 million objects, and 100,000 galaxies for researchers to explore.

The 80-terabyte data set comes from 2,480 exposures taken over six months during the experiment’s “survey validation” phase in 2020 and 2021. In this period between turning the instrument on and beginning the official science run, researchers made sure their plan for using the telescope would meet their science goals—for example, by checking how long it took to observe galaxies of different brightness, and by validating the selection of stars and galaxies to observe.

“The fact that DESI works so well, and that the amount of science-grade data it took during survey validation is comparable to previous completed sky surveys, is a monumental achievement,” said Nathalie Palanque-Delabrouille, co-spokesperson for DESI and a scientist at the Department of Energy and Berkeley Labs.

“This milestone shows that DESI is a unique spectroscopic factory whose data will not only allow the study of dark energy but will also be coveted by the whole scientific community to address other topics, such as dark matter, gravitational lensing, and galactic morphology.”

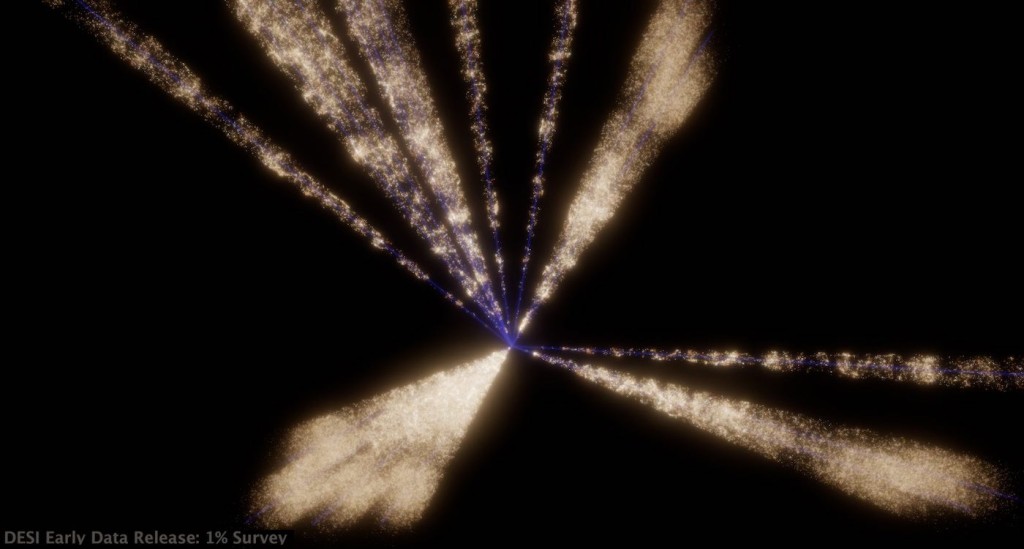

DESI uses 5,000 robotic positioners to move optical fibers that capture light from objects millions or billions of light-years away. It is the most powerful multi-object survey spectrograph in the world, able to measure light from more than 100,000 galaxies in one night. That light tells researchers how far away an object is, building a 3D cosmic map.

The survey image above represents just 1% of the total area of the universe DESI will study and map.

Two interesting finds have already surfaced: evidence of a mass migration of stars into the Andromeda galaxy, and incredibly distant quasars, the extremely bright and active supermassive black holes sometimes found at the center of galaxies.

“We observed some areas at very high depth. People have looked at that data and discovered very high redshift quasars, which are still so rare that basically any discovery of them is useful,” said Anthony Kremin, a postdoctoral researcher at Berkeley Lab who led the data processing for the early data release.

OTHER SPACE NEWS: Astronomers Discover Hundreds of Mysterious Filaments Pointing Towards Our Milky Way’s Massive Black Hole

A red-shift quasar refers to the phenomenon of “red-shift,” when the rapid expansion of the universe stretches light from distant objects into longer and longer wavelengths. The James Webb Space Telescope was designed with this in mind, and so two of its cameras see into the infrared light spectrum.

“Those high-redshift quasars are usually found with very large telescopes, so the fact that DESI – a smaller, 4-meter survey instrument – could compete with those larger, dedicated observatories was an achievement we are pretty proud of and demonstrates the exceptional throughput of the instrument.”

“If you looked at them, the images coming directly from the camera would look like nonsense – like lines on a weird, fuzzy image,” said Laurie Stephey, a data architect at the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center, which processes and stores DESI’s data.

MORE ASTROPHYSICS: X-rays and Webb Telescope Provide Dazzling Views of Space Invisible to the Unaided Eye

“The magic happens in the processing and the software being able to decode the data. It’s exciting that we have the technology to make that data accessible to the research community and that we can support this big question of ‘what is dark energy?’”

There is plenty of data yet to come from the experiment. DESI is currently two years into its five-year run and ahead of schedule on its quest to collect more than 40 million redshifts. The survey has already catalogued more than 26 million astronomical objects in its science run, and is adding more than a million per month.

WATCH a brief video of the data collection…

Don’t Forget To SHARE This Astronomy News With Your Friends…