Design students in Colombia have harnessed the porousness of moss to design a water filter that can trap microplastics.

Over the two-month product life of the filter, it can trap 80 grams of microplastics, sparing the drinker’s biology from consuming the equivalent of 16 credit cards.

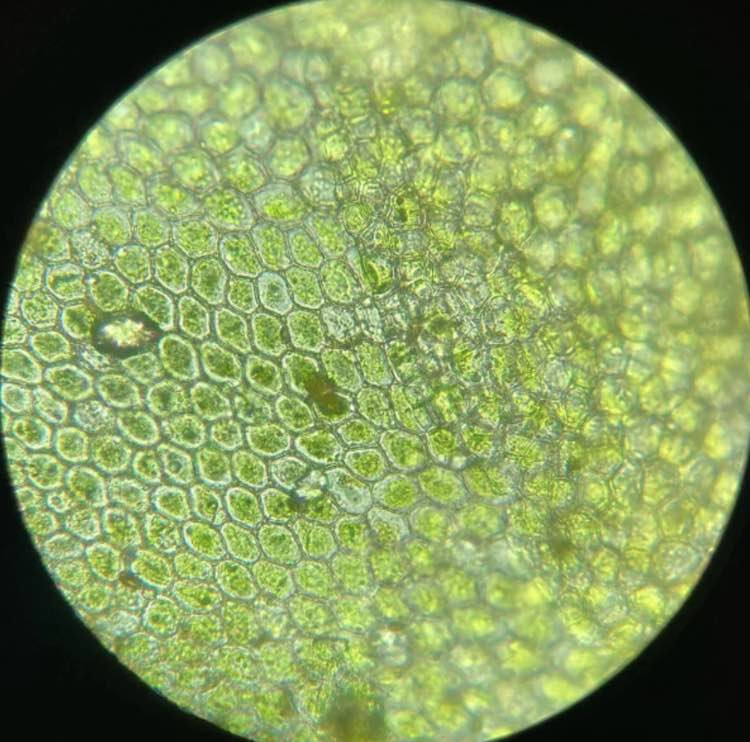

The design comes from the remarkable ecosystem high in the Andes Mountains called the Paramo. Hiking in this mountainous region is done either on rock, or what feels like marshmallows. The biosphere is covered in layers of moss species which absorb, filter the water, and send it down mountain streams where it’s scientifically found to be good to drink for around 40 million people across northern South America.

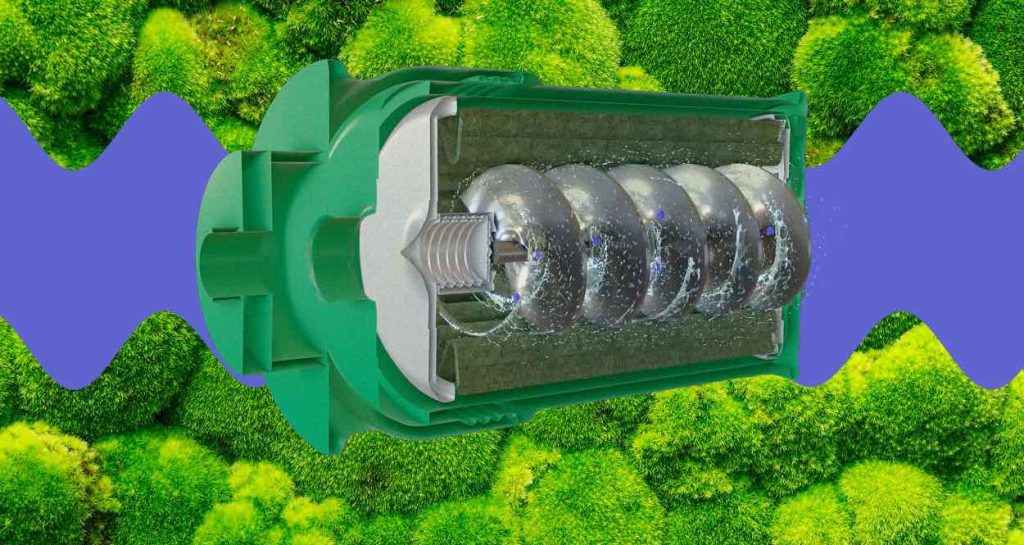

Called MUS(T)GO, the filter, designed by students at the University of the Andes, won the annual Biodesign Challenge Summit.

While microplastics so far haven’t been proven to be harmful when ingested by humans, scientists aren’t waiting for confirmation. Researchers around the world are testing new methods to recapture the bits—from Texans using ocra, to robots that can vacuum them from beaches.

MUS(T)GO uses a steel spiral shaped like an Archimedes screw, inside which is a variety of sphagnum moss grown in nurseries outside the internationally-protected Paramo zone.

RELATED: Mussels Can Help Filter Microplastics Out of Our Oceans Without Any Harm to the Molluscs

The design team hasn’t unveiled a prototype, but the filter is designed to be used by poorer communities who don’t have access to a filter, or by gardeners who can fit the filter on the end of a hose. Because the moss would become embedded with microplastics, the team wants also to try to invent a way to turn the discarded filters into a bio-plastic.

“[Moss] is such a little organism, and it does so much for the entire ecosystem,” Maria Paula Osorio, a student at the Bogota university who designed the product, told Fast Company. “We understood how amazing this natural creature is and wanted to do something that matters.”

Many state-of-the-art recycling methods for plastic are actually being derived from the natural world. Currently two bacterial enzymes are found to dissolve the complex molecular bonds that link the monomers into PET plastics.

While nature seems powerless to prevent plastic pollution, through her incredible diversity we might just be able to do it on her behalf.

SEND The Green News to Eco-Friends on Social Media…