Over the last two decades, a secret institution has gone largely uncredited with some fairly remarkably achievements in animal conservation.

But as well as potentially offering the only chance for the northern white rhino’s survival, the “Frozen Zoo” at San Diego has already given a second chance to animals as close to and (some times over) the brink as possible.

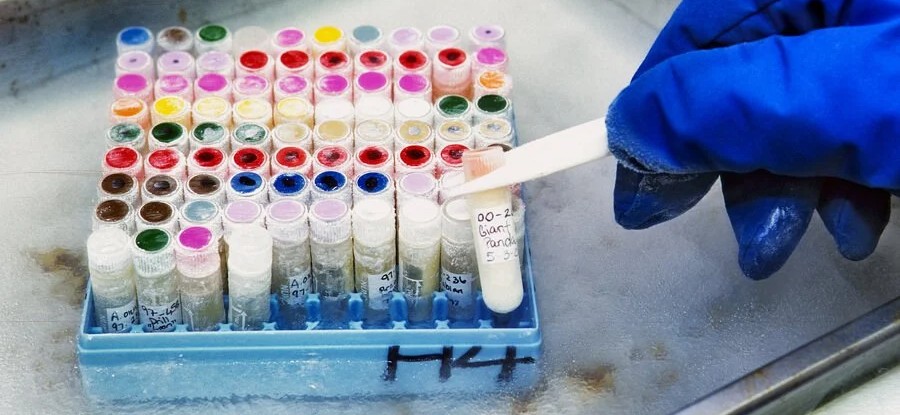

San Diego’s Frozen Zoo is not a place to see polar bears and penguins, but rather a cyrobank of cells from endangered animals from around the world.

It was their stored genetic material that has led to the cloning of the critically endangered and undomesticated Przewalski’s horse in 2020, an Indian Guar—a species of humpbacked wild ox in 2013, a Banteng, a species of cattle found in Southeast Asia in 2003, and the black-footed ferret, also in 2020.

The Frozen Zoo has been around for 50 years. Started in ’72 by a biologist named Kurt Benirschke, above the door to his lab was a sign that prophetically read “you must collect things for reasons you don’t yet understand,” referring mostly to skin cells, stored in Frozen Zoo at -320°F.

RELATED: We Finally Rid An Island of 300,000 Rats – Now Everything is Blooming

Some scientists have determined that the biodiversity of life on Earth may fall by around 1 million species in the next century. To this end, the work of institutions like Frozen Zoo is becoming even more critical. CNN reports they are already saving eggs and sperm of animals like the cheetah—not yet recognized as endangered, but at a high risk of doing so.

In total they have 10,500 individual animals from 1,220 species, and currently among them is the only available frozen material from male northern white rhinos—12 to be exact, from which they’ve managed to create stem cells—which could be used to create sperm to fertilize an egg, which would then have to be carried by the closely related southern white rhino subspecies.

LOOK: Chinook Salmon Introduced to Mountain Streams Not Inhabited for 100 Years

GNN first reported on the Frozen Zoo with the birth of Elizabeth Ann, a black-footed ferret.

Today, all black-footed ferrets are descended from seven individuals, resulting in unique genetic challenges to recovering this species. Cloning may help address the issues of genetic diversity and disease resilience in wild populations. Without an appropriate amount of genetic diversity, a species often becomes more susceptible to diseases and genetic abnormalities, as well as limited adaptability to conditions in the wild and a decreased fertility rate.

Frozen Zoo isn’t the only organization that cryobanks endangered animals. Nature’s Safe, founded by Tullis Matson, also collects cells of the same types for the same purpose.

Cryobanking receives little of any kind of funding, and most are working on shoestrings. However Matson told CNN he sees the greater challenge, since private donations are there, to be inter-program coordination.

MORE: Watch the Moment a Lost Panther Kitten is Reunited With Mother, Thanks to Florida Wildlife Officials

“The task is enormous, nobody can do this on their own,” says Matson. “There’s a million species at risk. We need 50 different genetic samples from each, so that means 50 million samples; for each of those, we need five vials for each sample, so that’s hundreds of millions of samples that need to be stored.”

It’s no small task, but cryobanking endangered species’ cells has all the qualities of a “bigger than you, bigger than me” challenge, no doubt attracting talented individuals. If one or two more species, particularly the rhino, whose coming extinction was heralded solemnly by news stations around the world, could be revived via Frozen Zoo or Nature’s Safe, it could draw the attention the workload deserves.

SHARE the Hope; Share This Story With All Your Pals…