Reprinted with permission from World at Large, an independent news outlet covering conflict, travel, science, conservation, and health and fitness.

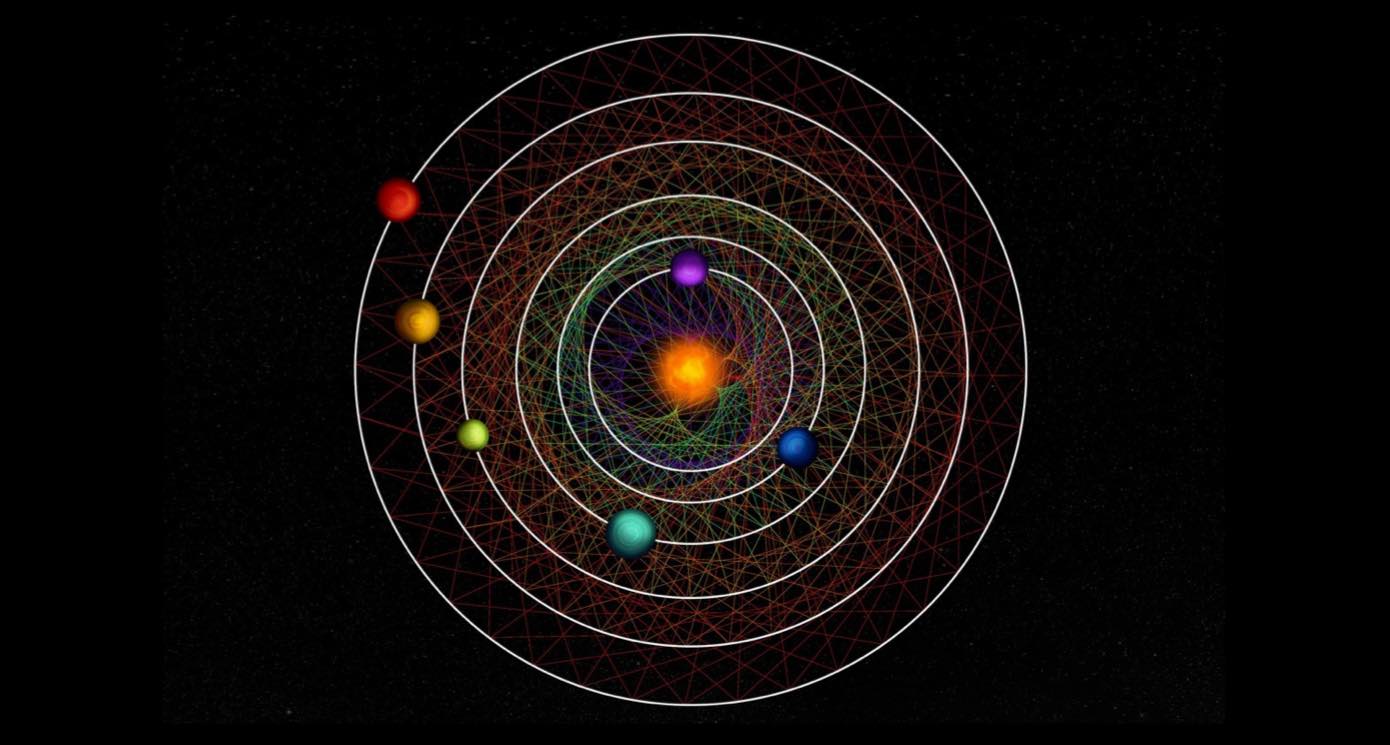

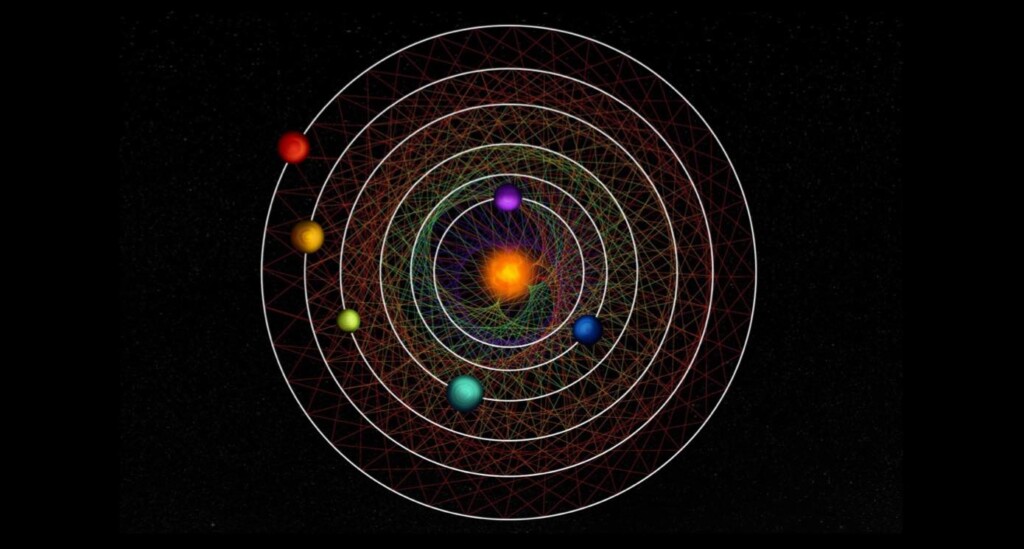

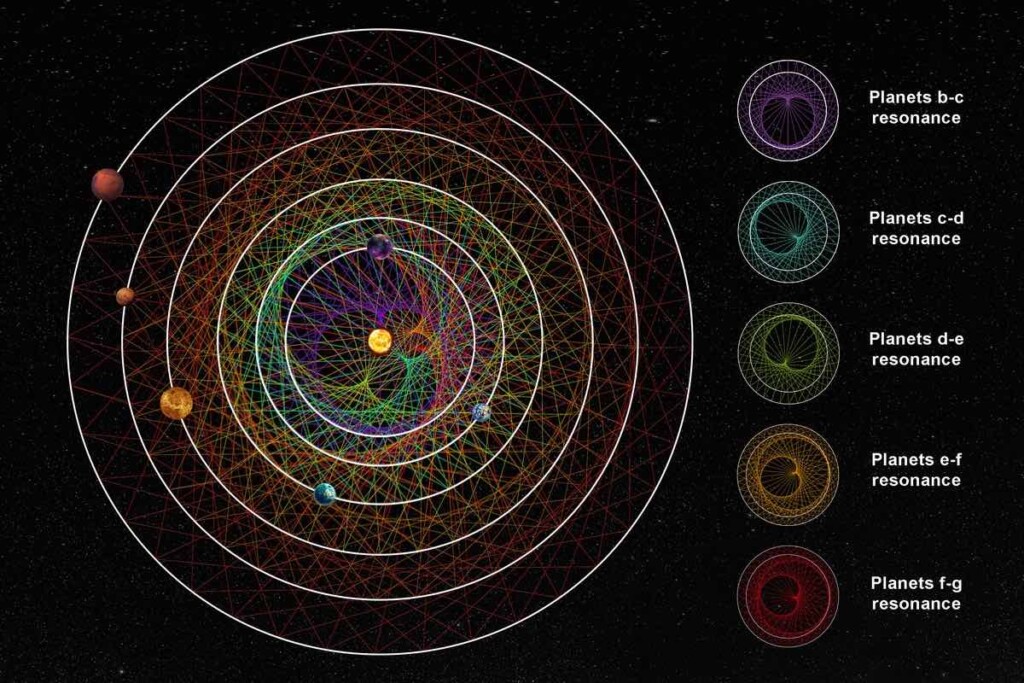

Scientists have discovered 6 exoplanets orbiting in perfect resonance around a star, meaning their orbits are synchronized. Such a phenomenon is only known to occur during the initial phases of star-and-planet system formation, indicating that little if anything has disturbed their eons-long ‘waltz’.

The bright star, HD 110067, was identified in the Coma Berenices constellation about 100 lightyears from Earth. The observations were first made by NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) in 2020 and 2022, and they revealed several dips in the star’s brightness at routine times. With additional observations from the the European Space Agency’s ‘CHaracterising ExOPlanets Satellite’ (CHEOPS), the signals were interpreted as six planets passing in front of the star.

Brilliant—6 more exoplanets to study—a fantastic find at most times, but these were special since follow-up research by a team of European astronomers has revealed the 6 planets are engaged in a dance, where for every 3 complete orbits one planet makes, the next one out from the star completes 2.

The way in which this happens is typified by the theory of star-system formation, whereby the evolving planets in an early system exchange torque with the protoplanetary disks and migrate towards their star. As they begin to move they pull on each other until they reach an equilibrium whereby the gravity of each one affects the others on top of the existing gravitational pull of the star.

“Here we have 3 to 2, 3 to 2, 3 to 2, and 4 to 3, 4 to 3 I think, if I remember correctly, and this is all connecting all the planets in a resonance configuration, and by chance it happened that the inner planet made 6 orbits while the outer planet makes 1,” says co-author on the paper describing the sextuplets, Adrien Leleu at the University of Geneva, Switzerland.

“Once the disks are no more, you can break the resonance by some star passing by, or another massive planet, or any kind of instability that can arise. So you can break resonance during the years of evolution but you cannot easily form them, I mean we don’t know of any mechanism that would form them after the disk dissipates,” he adds. “So it means they are formed billions of years ago and they remain in this very precise very ordered orbital dance”.

As a result of the delicate nature of resonance configurations, many of the multiplanet systems known to astronomers are not in resonance, but look close enough that they could have been resonant once. However, multi-planet systems preserving their resonance are rare, with senior author Raphael Luque estimating that around 1% of multi-planet systems retain resonance.

Worth their weight in gold

The planets themselves are relatively normal. They are termed “sub-Neptunes’ which describe non-rocky worlds about 1 to 2 times the mass of the Earth, and while the team identified 6, they admit there could be more.

The rarity of their dance was noted by Dr. Hugh Osborn, author on the paper and of a video matching the orbital dance to musical chimes to help explain it.

“These transiting systems are worth their weight in gold because these are the systems where because they pass in front of their star you get all this information,” he told the press in a video conference. “You get a very precise radius, you get the starlight filtering through the atmosphere which enables you to measure the atmospheric constituents, so that’s why this is such an important system”.

One of the most fascinating and immediate questions that arose was what can science glean from the HD 110067 system that might help discover what happened to the resonance in our own solar system, if there ever was such a configuration. Research has shown that the early solar system was populated with dozens more planetary bodies than now, and that collisions and the gravitational force of Jupiter reduced their number significantly.

The inclination between each planet in the orbital plane is very consistent, varying by less than 1 degree, further suggesting the system has been a very peaceful place for its 4.3 billion-year history.

“Even in our solar system, those resonances appear to have not survived, so having a system in which they have for billions of years—it’s going to tell us what are the requirements that at least for a star, that forms with its planets, must have in order to preserve these conditions,” said Dr. Luque at the University of Chicago.

ANOTHER DISCOVERY: NASA Just Found an Ocean World with Atmosphere–The Best Place to Look for Life in Our Galaxy

“Maybe learning about this one will tell us about why our solar system doesn’t have one; is it because of Jupiter and Saturn, because they took all of the material available and didn’t let the smaller planets to form? So all these questions we aim to answer by studying this system in detail.”

VIBRATE Your Science Pals on Social Media By Sharing This Fascinating Planetary Dance…